A Voice in the Dark: Subversive Sounds of the Living Newspapers and the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936-37

By Jeremy Woodruff

Abstract

Technologies of the day such as radio, film and public sound amplification were crucial to the production of an immersive effect in both theatrical and political demonstrations of the 1930s. The dynamics of amplification were pushed to extremes in order to engulf the public and get them caught up in a spirit of revolt alongside actors in theatrical productions and strikers on the front lines in labour battles. In this article I will examine two case studies of live subversive sound techniques inspired by new media of the time. These traverse the theatrical and political realms of worker’s culture of the late 1930s: the Living Newspapers of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theatre Project, and the Flint sit-down strike of 1936-37. The two interconnected moments in US cultural history reveal a startling ingenuity that, driven by the aesthetics of theatre, radio and film, moved the public and changed the course of American politics.

Keywords

Living Newspapers; Flint sit-down strike; Theatre; Labour; 1930s; Sound; Protest.

Flint sit-down orchestra, 1937. Source: The Spiritual Pilgrim, Miles H. Hodges.

Technologies such as radio, film and public sound amplification were crucial to the production of an immersive effect in both theatrical and political demonstrations of the 1930s. In this article I will examine two case studies of live subversive sound techniques inspired by new media of the time: the Living Newspapers of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Theatre Project, and the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936-37. These examples, which traverse the theatrical and political realms of worker’s culture in the late 1930s, demonstrate how innovative sound techniques were vital for political change. As such, they provide an analysis of how both theatrical and political activism used sonic immersion as affective contagion in political demonstration.

In these contexts, immersive forms of amplification were often utilised to engulf the general public and submerge them in the spirit of revolt alongside actors in theatrical productions and strikers on the front lines in labour battles. This immersive sonic effect functioned in four different arenas: Sonic immersion made theatrical productions more life-like and hard hitting; made protest events more theatrical and contagious; made the social life and culture of the unions more cohesive; and extended into the urban soundscape, announcing and advertising the events in order to demarcate and herald change. These sonic tactics encouraged the strikers and their families, won escalating popular support and ultimately contributed to positive outcomes for union workers involved in direct action.

Sonic ‘Immersion’ is appropriate here; it describes not only a three-dimensional listening experience, but also gestures to an absolute corporeal and cognitive engagement. To understand how dimensions of sonic performance occurring at the intersection of theatrical and political demonstration multiplied this immersive potential, this paper will cover a number of tangentially related subjects: I first describe the general character of agitprop and left-wing theatre in the 1930s and identify factors that encouraged the development of innovative sound techniques in this context. I then proceed to discuss the use of innovative sound techniques in the context of the worker’s strike, outlining how their use provides alternative insights into the conditions of the strike. Forms of new media are then explored, both in the context of political events of the time and in terms of their use in the theatrical productions of the Living Newspapers. These are explored in the context of the productions themselves and in their extreme influence, alongside agitprop and left-wing theatre generally, on the worker’s strikes. Finally, I bring the threads of this discussion together to theorise the significance of my research for a concept of immersive sound in politics and political activism more generally. Through a careful listening to the immersive sounds of agitprop, left-wing theatre and political broadcasts, it is possible to appreciate the full significance, subversive potential and virtuosity of the unusual aesthetics found both in the Living Newspapers and the Flint sit-down strike.

The confluence of seemingly discrete events explored in this paper present an argument for the re-evaluation of culture in socio-political movements. Some of what has previously only been treated as direct action, can be understood as vital forms of communal composition, possessing a relational aesthetics1 in their own respect. The significance of such protest events, not only in their connection to, but as artistic participatory events, has been overlooked. Also, the possibilities they present, both for the political struggle for individual freedoms and for participatory sonic art, is largely neglected.

Agitprop and worker’s theatre in 1930s USA

Worker’s theatre thrived during the Great Depression, facilitated by worker education programs where theatre was a central part of the curriculum. The more workers were educated at these institutions, the larger the audience for worker’s theatre became, and the greater their readiness grew to mobilise in response to what they experienced on the worker’s theatre stages. In the 1930s, this ‘feedback loop’ of radical education/theatre was at the heart of protest music’s power to galvanise workers into action. This model for (re-)education through theatre came from the concept of Soviet agitprop and, though only one facet of the worker’s theatre in the 1930s, was extremely important to the US labour movement (Hyman 1997).

Agitprop, a contraction of ‘agitation’ (an incitement to action by appealing to the emotions of the audience) and ‘propaganda’ (politically aimed mis/information) was first used to refer to the Agitation and Propaganda Section of the Central Committee Secretariat of the Communist Party in the Soviet Union, established in the 1920s. Agitprop arrived in the USA in the 1920s and 30s, first through the German language theatre group, Prolet-Bühne and then via other immigrant theatre groups such as the Yiddish speaking theatre Artef, and the Hungarian Workers Shock Brigade.2 In 1930s America, the Russian revolution loomed large in recent history and politics. As a nation with practically no unemployment, The Soviet Union presented an example to many, emerging in stark contrast to the USA where the unemployment rate averaged around 18% over the course of the decade (Romer 1986). After the crash of 1929, political activism – specifically anti-fascism and anti-capitalism – was of special concern to the arts, and how they should be integrated into artistic activity became a central debate.

The agitprop style entailed a rapid-fire declaiming of lines in a rhythmic fashion, often in chorus, combined with demonstrating with effigies. Gymnastics and music were customarily integrated into the plays (which could perhaps more often accurately be described as a series of skits). Agitprop also included parody; a high point of the Shock Troupe’s3 output was in 1933 at the Chicago World Fair with their piece World Fair ridiculing the festival as a “celebration of capitalism” (Levine 1980). Lured by the sound of a brass band, visitors were treated to members of the National Recovery Administration being presented as freaks, Herbert Hoover as “the world’s fattest man” and the bearded ladies as the “daughters of the American revolution” (Levine 1980; Mally 2008).

Beginning in 1934, however, a new ‘realism’ in the worker’s theatre signalled a split from the aesthetics of agitprop, while retaining its participatory philosophy. Stanislavski (the famous Russian actor and director) provided the theoretical basis for a type of training that spread throughout the country via the Worker’s Theatre League. Mainly developed by the Group Theatre, the Stanislavski technique4 was enhanced by them into the modern form, and also became what is now called ‘method acting’ (Levine 1980). Method acting was based on remembering emotion from lived experience. It is perhaps no wonder that method acting developed in this period, where there were so often only small differences between worker’s lives and those of the characters they portrayed on stage. In many cases, dramatic classes at labour schools ran workshops for plays that were also intended as rehearsals for real-life labour actions (Hyman 1997). Similarly, agitprop workers were, by and large, not called upon to ‘perform’ in a traditional sense. Characters were usually named after a concept or group of people, for instance ‘Capitalism’, ‘Boss’, or ‘Farmer’. By the 1930s the character ‘Radio’ also appeared in some plays as one of Capitalism’s servants (Friedman 1979) and, so too, the ‘Loudspeaker’ character would soon emerge in the Living Newspapers theatrical productions. The style thus fit perfectly into labour culture largely because it was easier to get workers who had reservations about their lack of professional acting ability to participate in it.

In many cases, therefore, worker’s theatre more closely resembled political demonstration than traditional drama. In some instances the political nature of the theatre directly precipitated political action. This is particularly evident in the premier of Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock (1937), where the performance commenced in the streets on the way to a new location when the police closed down the original venue. In other instances political organisation precipitated theatre; the production of Pins and Needles (1937) was staged by and for members of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union while they were striking, but it became so successful when mounted as a Broadway production that the cast quit their jobs to perform it eight times a week (Denning 1997). As Stuart Cosgrove writes of the massive endemic strikes in the 30s: “[it was] increasingly difficult to determine the blurred boundaries between the drama of direct action and the stages of political theatre” (1985a, p.13).

The great breakthrough for the Group Theatre and a definitive moment for left-wing theatre in general, came with Clifford Odet’s Waiting for Lefty (1935), which told the story of an actual taxi strike. It was produced in countless theatre associations across the United States, as well as in Moscow, London and Glasgow. In the play, actors are planted in the audience to enact fights and other dramatic moments. This was a tactic to encourage the audience to involuntarily participate in the play, and it succeeded on several occasions.5 The real life stories of actual personalities and relationships from the testimony and involvement of strikers were integrated into the play and their problems were dramatised. At the premiere, the audience spilled out of the theatre shouting, “Strike! Strike! Strike!” echoing the words that conclude the play. As such, Waiting for Lefty was a crucial point of reference for the Living Newspapers and for many other subsequent left-wing theatre plays.

When Roosevelt initiated the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1935, a state program called the Federal Theatre Project (FTP) drafted many of the key figures in the worker’s theatre movement. Naturally the FTP’s approach to theatre and its goals were therefore largely informed by agitprop’s legacy and by that of the Group Theatre. The official goal of the FTP, however, was to put theatre people and musicians back to work. It often sponsored projects that employed huge casts and staff. The Living Newspapers, the flagship project of the FTP, was no exception.6 At its zenith, casts would include two hundred or more actors and a team of sixty-five writers who would search for information about a specific political topic, largely drawing on recent media articles for research (Mally 2008). In One-Third of A Nation (1935) the theme was the poor living conditions in urban ghettos; in Triple-A Plowed Under (1936) it was starvation in America. This documentary method of the Living Newspapers created an entirely new and alternate format for bringing current news information with a radical left-wing historical analysis to the people. The pace of the plays, with their accompanying film, slides, music and sound effects, replicated radio news and cinema newsreels, offering a sophisticated multi-media and collage aesthetic (Jarvis, 1994, Mally 2008). As we will come to see, the Living Newspapers also aimed to immerse and surround its audience, to a hitherto unprecedented degree, in a rich soundscape made up of everyday sounds. The Living Newspapers were beginning to be active in multiple cities from coast to coast when they were shut down in 1939. Nevertheless, they had already had an enormous influence on American theatre; In New York alone One-Third of a Nation played to a total audience of 111,000 people during its 1938 run (Arent 1938).

The sounds of labour and broadcast propaganda in the 1930s

In the 1930s, before restrictive labour laws were introduced and much local legislation regulating public amplification was passed,7 strikers were emboldened, in the spirit of agitprop, to employ new performative tactics in their demonstrations. In particular, the workers turned to the emergent potential of broadcasting and amplification, using both to effect in the sit-down strike and in surrounding demonstrations. Whether the strikers and organisers were cognisant of the effectiveness of the aesthetic dimension of the unusual sonic methods in question, and to what extent they composed them and how, is an under-valued question in cultural histories and hence, barely documented and little researched. However, this paper gathers evidence to suggest that the inventive modes of propaganda and defence used during strikes were not just tactics induced by the exigencies of a labour face-off, but creative and cultural products. These in turn were largely inspired by the avant-garde tendencies in theatre that infused the labour culture of the 1930s. These tactics were community statements of class-consciousness, bolstered by popular media forms and calculated for maximum impact on the public-at-large.

The sit-down tactic was used to great success in Flint, Michigan, during a 44-day strike that commenced on December 30th, 1936, when workers took over the Fisher Body Plant No. 1. Their action inspired a further wave of successful sit-down strikes throughout the country.8 By occupying the factory for the whole duration of what is called a sit-down strike, workers could ensure that no ‘scabs’ took their place at the machinery. Among other advantages, in a sit-down action it became nearly impossible for the police to claim that the strikers were the aggressors (Shogun 2006). From the very first, noise was used as a tactic in the Flint sit-down strike. When the sheriff first tried to serve the judge’s first injunction to evacuate the premises on behalf of GM, all three hundred men who had sat down in the building four days earlier made so much noise that he could not even hear himself (Fuoss 1997). As many examples as there were in the Flint sit-down strike of spontaneous outbursts of aggressive and disorganised disruptive noise of this sort, it is to the immersive, broadcasting uses of sound that I wish to turn to. Noise, amplification, film and radio have a well-documented and theorised potency in political domination as both catalyst and deterrent in insurrection.9 Here, the workers seized what power they had over amplification in privatised space and took advantage of the relative independence of the airwaves on a local level to stage a powerful and theatrical series of rebellious events.

The sound car

The deployment of the sound car was a frequent tactic of labour in the 1930s.10 Following the first meeting of the sit-down strike, a motorcade of up to one thousand automobiles paraded through the streets of Flint and drove up to the striking plants to announce the action and show support. They honked horns past cheering bystanders and were led by a loudspeaker-mounted car that broadcast announcements and instructions.11 Later, in skirmishes with company officials and the police, the sound car was also used to coordinate worker defences and to lead slogans, chanting and singing during the battle (Fuoss 1997). Both strikers and police understood the crucial tactical importance of these mobile sonic broadcasts. Six other union cars protected the sound car when going out with the union auto cavalcade and it was the first target that the police attacked in a confrontation that became known as the ‘Battle of the Running Bulls’ (Fine 1969).12

In the film With Babies and Banners (1979) Sherna Gluck, a striker’s wife, describes how the sound car13 was instrumental in victory over the police in this confrontation.

The radio had announced to the city of Flint that a riot had broken out down on Chevrolet Avenue in front of Fischer Two and a revolutionary situation was developing and you can imagine what an electric shock that was for Flint …The populace of the city drove down just as they do for a fire at any time to gather in back of the police and to watch and observe this…the men [strikers] were speaking out to the people behind the police lines explaining what we’re fighting for, what had happened, how the battle broke out. When this happened we had only the sound car broadcasting to those people…Victor Reuther [organiser and brother to Walter Reuther president of the UAW] and many of the others were there that night on the sound car… and finally Victor came up to us and said, ‘maybe we’re going to have to lose this battle but we won’t lose the war’… but the batteries on the sound car [were] running down. And I said, ‘Oh let me speak then Victor’…so I got up on the sound car and I was desperate, and I decided to appeal to the women of the city of Flint at that point, …I got up there and I said ‘women of the city of Flint, break through those police lines and come down here and stand with your husbands, your brothers, your sons and your sweethearts…they’re firing into unarmed men, the police are cowards!’…this was electrifying because they thought there were no women down there until this woman’s voice came over the line…and the women did break through that night…and as soon as the women went marching down into the middle of the battle, the police didn’t want to be accused of shooting into the backs of unarmed women…and that wound up the battle that night… and then we lighted the bonfires and we sang songs all night long. (Grey 1979)

Broadcasting and Amplification

This first-person account also illustrates how strikers relied on local radio for news and to mobilise in physical space.14 In the 1930s, when there were still a significant number of local independent stations,15 strikers could depend on public alerts by radio. As Gluck describes, news of a confrontation was a primetime event, paramount to a local catastrophe, and its broadcast increased the size of the crowd that would potentially assemble.

By the 1930s electronic amplification was a common feature of audio culture all over the world. This was represented most abundantly through the medium of radio. As Emily Thompson notes, “stadium audiences were accustomed to hearing ‘radio sound’ emitted from loudspeakers, as the use of public address systems for large gatherings of all sorts was now well established” (2002, p.241). From its early inception, therefore, “radio [could] be best understood as a technologically extended branch of agitation” (Lovell 2011, p. 604). In the early days of the USSR, for example, the presenter’s voice in Soviet state holiday broadcasts would regularly be accompanied by “hurrahs, salutes, songs, and sheer background hum” (ibid). In Nazi Germany the National Socialist propaganda machine aggressively promoted Volksgemeinshaft (national community) through music, lectures and particularly radio broadcasts. Goebbels dubbed the radio the “spiritual apparatus of the nation” (Birdsall 2012, p.115) and the Nazis placed special emphasis on public rituals designed to engulf the public. Radio broadcasts played a crucial role in these. As Birdsall writes, “through the realisation of sensory overwhelming and spatial omnipresence, these party rituals provided a template for the creation of affirmative resonances that could sound out the entire public space of the city, saturating the ears and bodies of the people” (2012, p.56). During the war, radio addresses known as Sondermeldungen interrupted regular programming to give special news about Nazi victories, and included all of these elements, causing everyday life to come to a halt for their duration.

As such, Radio and amplification in the 1930s was ascribed with an almost supernatural power over the populace. The personal bonds listeners could form with the disembodied voices of personalities were an uncanny new phenomenon (Lenthall 2007). David Goodman writes: “1930s educational material about the dangers of propaganda posited a connection between extensive background radio listening and an emotional rather than …critical response” (2010, p.26). While radio was kept under tight state control in Stalinist Russia, the perceived intrusiveness of radio advertising sparked debate and legislation in the USA. Ventura Free Press publisher H.O. Davis was quoted famously in 1932 as saying, “this ‘personal, emotional appeal’ of the radio voice …makes it the most potent instrument for good or evil…and loads the microphone with social [dynamite]” (Stamm 2010, p. 231).

Living Newspapers

In the 1930s, radio broadcast was still so new that it was often defined in terms of established media formats and print newspapers in particular. In 1935, newspapers owned twenty percent of American radio stations16 and often announced their paper’s name after the radio’s call letters or otherwise reminded their listeners of the affiliation to the home paper at regular intervals (Stamm 2010). Almost a quarter of respondents polled in 1938 got their news exclusively from the radio, while an additional twenty-eight percent got their news from a combination of the radio and newspapers (Douglas 1999). It is possible that the way in which news was seemingly ‘brought to life’ in the transition from the printed page to live radio formed an inspiration for the ‘Living Newspapers’. In any case, new modes of news reception – over radio or as a combination of print with live broadcast – are echoed in productions of the Living Newspapers. In fact, not only were current events depicted by the characters on stage, but a series of alternative newspapers were also distributed at many productions (Federal Theatre Bulletin 1936). However, more than anything else, the narrative voice of the Living newspapers bears a resemblance to the expository form of radio broadcast.

The voice in the dark

A voice emerging from the dark is a recurring theme in theatre of the thirties, a reference to radio, amplification and the political power of the acousmatic radio transmission.17 Such a voice had a particularly heightened dramatic emphasis and reception during the early history of radio. A disembodied narrative voice could even become the definitive and most popular quality of a radio show. This was the case in the Detective Story Hour (1930 – 1937) where the famous line, “who knows what evil lies in the hearts of men?…The Shadow knows!” was spoken by an omniscient character. This voice had no connection with the characters in the plot but was simply a framing device to provide consistency where otherwise different unrelated detective stories were presented in each episode. In a Living Newspaper production, with casts in excess of two hundred actors performing in dozens of short vignettes, a disembodied narrative voice-over was crucial to tie together the plot with expository dialogue. Originally named “Voice of the Living Newspapers,” the narrating voice of the plays was later changed to ‘Loudspeaker’ in productions from Power (1937) onwards. In many ways, this narrator was a personified subversion of mass media, reclaiming the acousmatic voice of authority heard on public loudspeakers and state controlled broadcasts.

There was a precedent for this voice. Morris Watson, the production manager of the Living Newspaper Unit cites Clifford Odets’ technique in Waiting for Lefty of immersing the public in the action of the play by putting actors in the audience as a good model for the Living Newspapers to emulate, saying, “Instead of confining all the action to the stage, [Odets’] characters often played from the house” (Watson 1937, p.3). To be more specific, Odets wrote “In the climaxes of each scene, slogans might very effectively be used – a voice coming out of the dark…It is very valuable in emotionally stirring an audience” (Odets 1935 in Cosgrove 1985b, p.352).

News flash: Sound in the Living Newspapers

This objective was accomplished by the use of new media for acoustic amplification.To immerse the audience, the Living Newspapers experimented with sound projection in the theatre. As Harold Burris-Meyer, sound engineer of the Living Newspapers (and later the first vice-president of the Muzak company),18 claims:

[E]lectronically-controlled sound… gave you an opportunity to approach the emotions of the audience which you wouldn’t have without such control. And I had been undertaking to control any sound, to produce any sound from any source or no source or a moving source, a sound with any characteristics such as direction, distance, reverberant characteristic, and loudness. Now that’s a rather large order but I had been using that in experimental productions at Stevens Institute of Technology…The concept of the voice of the Living Newspaper got expanded as more plays were produced…we used the sound of an aircraft as it approached and circled over the audience and then landed. And the place it landed was up stage left…it was a very realistic reproduction. However the voice of the Living Newspaper [“Loudspeaker”] was really the important element and this voice was reproduced [from all directions at once]. That is, the voice was there, but no place to which you could point. And this made it at once intimate and all pervasive…All you needed to do was to make it come from everywhere…in the Ritz Theatre where we worked a good deal, we had loudspeakers which were pointed up at the ceiling so that the audience heard the sound as reflected down from the ceiling. And since one’s sense of direction is not accurate in altitude, since you can’t tell very well…the audience found it rather easy to accept what was logical (Burris-Meyer 1977, p1-3).

In this case Loudspeaker’s voice came down from on high, like the voice of God, or like a voice in one’s head, at once everywhere and nowhere.19

The Loudspeaker character had additional special properties. Concerning its new role in One-Third of a Nation, director Hallie Flanagan wrote, “The device of the Loudspeaker must be given another dimension…it must be a member of the cast at one time, the voice of the audience at another” (Flanagan 1938a). Morris Watson also notes that not only was Loudspeaker, “an ideal source of establishing time, place …and descriptive narrative,” but that “when certain expository scenes are shown, Loudspeaker can become the voice of the public at large – posing questions that are the un-crystallised opinion of the layman.” (Watson 1937, p.4) Many times the voice of Loudspeaker is a literal reference to radio20; at other times, as above, it was meant to represent the interior voice of the listener’s psyche. Furthermore, the border between Loudspeaker as narrator, and loudspeaker as electronic amplification in the manner of live radio sound effects, was sometimes trespassed. While writing about Loudspeaker the narrator, Morris Watson continues,

Another interesting use of the loudspeaker is that of conveying crowd noises. When an atmosphere of panic or hysteria needs the accompanying element of sound, the surplus forces of actors ad lib into microphones, augmenting the excitement visible to the audience. All other sound effects of the sort used in radio: airplane, mechanical, motor etc. can be fed into the loudspeaker (Watson 1937, p.4).

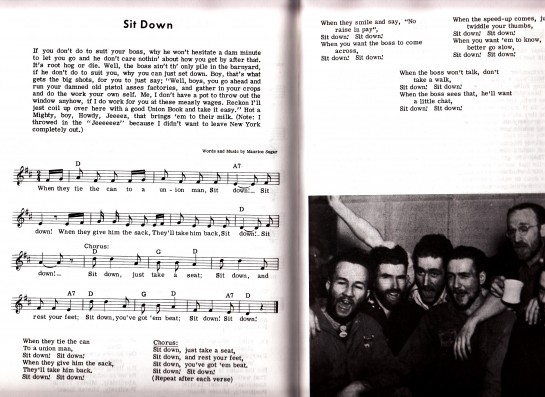

Double turntable

More innovative technical means were developed to deliver the rapid-fire sound effects necessary to keep up with the demands of the Living Newspaper’s fast paced collage techniques. Leslie Phillips describes a dual turntable, the construction of which is found detailed in technical diagrams and a documentary photo in the files of the Living Newspapers at the Library of Congress:

It was found that electrical transcriptions [recordings] were required following each other in quick succession, therefore double turn-tables of twelve inches in diameter were necessary, the whole set-up was specially wired for individual control or for mixing the two together or for fading one or the other in or out (Phillips 1938, p.1).

Living Newspapers Dual Turntable, 1936 Federal Theatre Project Technical Studies File, 1935-1939. Box 133 Living Newspaper, Sound Material. Library of Congress.

In the Living Newspapers the dual turntable was mainly used when sound effects and pre-recorded music were needed simultaneously (Burris-Meyer 1977). While double turntables were innovated previously in live “non-synchronous” sound production for cinema (Thompson 2009), the turntable employed by the Living Newspapers was portable and designed in such a way that both of the arms and pickups of the turntables could be used simultaneously on a single record if desired, simultaneously playing two different locations on the same disc (Federal Theatre Project Technical Studies File 1935-1939).

Steeling the show: The Flint GM sit-down strike of 1936-1937

As previously noted, political action often materialised as theatre and theatre as political activism in the culture of 1930s left-wing theatre. As such, the Flint sit-down strike of 1936-1937 was a remarkable instance where both kinds of performance influenced each other on various levels. The fact that the workers went to lengths to stage their own production of the Living Newspapers inside the occupied factory is an important indication of this.

While Morris Watson, the production manager of the Living Newspaper Unit, was visiting Detroit to give a lecture during the sit down strike, eighty workers approached him and asked him if he would come out to the Flint GM plant to oversee the production of their own Living Newspaper performance. “The struggles of the past six weeks will live again as workers re-enact on stage the valiant roles they have played in real life” read the advertisement for the two hundred strong production (Fuoss 1997, p.77). Coincidentally, the play The Strike Marches On was performed only moments after news of the victory of the actual strike spread, and thus embodied a befitting and rousing celebration of General Motor’s concession.

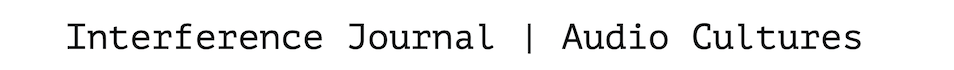

The performance used sound experimentally, “the first scene calls for monotonous, percussive music played at a faster and faster pace to evoke an assembly line and to suggest the company’s speedup of production” (Friedman 1985b, p.159). The striker’s use of familiar popular tunes extended the reach of their message. The two most prominent anthems of the strike were tunes borrowed from the cinema of the time. The Fisher Strike Song, which commemorates the beginning of the strike, was set to the tune of The Martins and the Coys which features prominently in the movie The Big Show (1936). In turn, the song The Battle of the Running Bulls used the tune from There’ll be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight . This song appeared in Virgil Thompson’s score to Roosevelt Administration’s documentary The Plow that Broke the Plains (1936), and also in Walt Disney cartoons in 1930-32, particularly one featuring Mickey Mouse as a fireman with the fire department. Could the tune be a reference to the workers having used a factory fire hose to shoot freezing water at the police during the battle, or was it just a coincidence? In any case, the Mickey Mouse cartoon parodied many older silent films that used the same tunes in similar comedic sequences; upbeat popular songs like these were generally used for the comedic sections of films in the 30s, and clearly Sit Down, another anthem of the sit-down strike, also uses this genre of comedic cinema music to make light of the police attack, transforming them with this filmic reference into keystone cop-caricatures. In many ways, applying new lyrics to popular songs is a valuable political tactic; once the new lyrics are circulated, the popular tune can continue to carry the supplementary message of protest in the listener’s mind with every subsequent hearing.

Sit Down Song, 1937. Source: Lomax A., W. Guthrie and P. Seeger., 1999. Hard Hitting Songs for Hard- Hit People. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Sit Down Song excerpt on Youtube The song referenced in the article

ends at 5’36”.

Concerts of a ‘sit-down orchestra’ were also held after the strike meetings at both the union headquarters and inside the factory Fischer No. 1 and were sometimes joined by the union choir (Fuoss 1997). The orchestra consisted of two mandolins, one guitar, one banjo, one accordion and three harmonicas. Posters advertised the nightly concerts, and at least once the orchestra even left the factory and went up town to give a concert (Fine 1969). Not only were the factory announcement loudspeakers utilised in these concerts, but additional loudspeakers were also erected, broadcasting the music to the outside world where audiences (mostly consisting of union members) congregated. Equipped for extreme volumes, the plant public address system alone would have been easily audible from outside while the factory machines were turned off during the strike.21 Meanwhile, after the meetings at the union headquarters, a union nightclub began with no cover charge. Different singers took the microphone at different times, to sing popular songs with the orchestra (Fuoss 1997).

It is worth considering the unconventional instrumentation of the sit-down orchestra; it is an example of the creative ability of the workers to use what they had at their disposal to generate unusual sound potentials. Furthermore, the instrumentation displays a particular theatrical flexibility of genre. Even though guitar, banjo, mandolin and harmonica regularly appear together with fiddle and string bass in a traditional bluegrass dance band22, the auto-workers instituted a wholly original and very American combination with popular overtones of three harmonicas and four plucked strings.23 However, the accordion could have also enabled ethnic folk influences to emerge, Polish- and German-American being foremost among them in the upper Mid-west. Thus the orchestra would have been able to cover both popular and folk styles. The sounding mechanisms of the three harmonicas would have blended with and strengthened the effect of those of the accordions. The combined detuned effect of all the plucked strings and mechanical reed instruments would have made ‘orchestra’ an apt rather than an ironic description of the ensemble.

On February 4th, 1937, thirty-five days after the beginning of the strike, the sonic interaction between the sit-downers penned up inside the factory and supporters outside reached a highpoint. The union had already planned it as Women’s Day, with the ladies’ auxiliary taking the leading role and of course including the striker’s children as well. However, as it became known that a second injunction would be served on that date, the union’s support forces escalated so as to intercept it. Hundreds of union supporters drove in from other parts of Detroit, Pontiac, Lansing, Saginaw, Toledo and Akron. After the Women’s Day parade through town in support of the strike, they all rallied at the main factory and began to march in formation. The number of picketers outside the factory was recorded at three thousand. As the time of the injunction approached, and with the National Guard surrounding the plant and awaiting a command, a strange scene ensued:

In the falling snow, several hundred men and women of the UAW…danced on the lawn in front of the plant to music played by the strikers’ orchestra from inside the factory. Coffee and sandwiches were served to the crowd, and the dancing continued into the night. A Detroit News reporter thought that the scene in front of the plant resembled a street carnival (Fine 1969, p.163). This standoff continued on throughout the following week, with the emergency brigades from out of town reinforcing the numbers. But instead of the injunction being served by the National Guard, on February 11th, 1937, General Motors instead capitulated to the union of the United Auto Workers (Fuoss 1997).

Outside the factory those listening to the sit-down orchestra would not have seen the players. You could call this a kind of acousmatic music. Listening in this way would have of course magnified the incidental sounds of the concert, conversation and other noises inside the factory to which, at a ‘normal’ concert, one’s attention isn’t drawn. It is not a wild conjecture then that the union members outside could have enjoyed listening not only to the musicians, but also to the camaraderie and even the commentary of the other strikers inside. Whatever the case, it is not hard to imagine how using the loudspeakers for performances was like a broadcast of their very own ‘sit down radio’ – a sonic demonstration and celebration of their control over the factory and all of its machinery. Considering these were workers who instigated a spontaneous production of their own edition of the Living Newspapers in the factory, it is wiser to risk the accusation of setting the bar of their imagination too high, than miss the opportunity to draw important connections; theatre and music coalesced here with new forms of media of the thirties to make a staggeringly original sound event; an inextricable part of protest tactics that changed the course of political history.

Resounding: Movements of early left-wing media

It is clear that a symbiotic relationship existed between left-wing theatre and communities of union workers. Forms of sonic immersion underpinned this connection, contributing to direct action and dramatising political struggles. Even before the striker’s victory, a different play was already being written about their struggle. Entitled Sit-Down! and composed by William Titus of the Brookwood Labour Players, it was intended to circulate among working class audiences and detail events of the strike. In a further illustration of the immersive ‘feedback loop’ in theatre education, Titus interviewed strike participants and used their actual names and stories in the play (Raymond 2009). Completed one month after the Flint strike, Sit-Down! was filled with music collectively composed and performed during the sit-down strike. The immersive use of sound is well articulated by the speaker at the end of Sit-Down!, who says, “Stop and listen and you can hear ‘em movin’ now! Get to beatin’ on a brake drum! Get to singin’! …keep marchin’! We the people are the power! Sing!” (Friedman 1985b, p. 159) Here, the message is clear: forms of sonic immersion are at the centre of the empowering experience and enactment of political freedom.

Labour education theatre efforts such as Sit-Down!24 manifested during protest as increased confidence and dramatic performance and this in turn elicited a heightened response from the community. Accounts of sound car demonstrations, theatrical performances and the spontaneous reactions of supporters to the sit-down orchestra are all powerful examples of this. So too, celebration of positive outcomes brought the union community even closer together. The strikers celebrated and announced their solidarity by staging musical events that in turn created affective resonances in civic space. The special bonds that theatrical protest fostered helped to enlist public interest and opinion as well as mobilising more workers to unionise and strike.

In all of these examples, audio culture is a link between historical and aesthetic events, providing a frame to better understand the nature of political confrontations and their dynamics. Blurring the borders of art and life, and educating and building a performative collective, can have powerful political and aesthetic payoffs. Prioritising the perception of sound, and hence the affective realm, rather than musical or non-musical format, structure or style, has consequences for both political and aesthetic analysis. This realisation in turn calls for a more thorough evaluation of activist history. The relational aesthetics of art and activism do not need to be disentangled here, but innovative artistic activity should be recognised and understood on its own terms.

It is perhaps more important now than ever to look to the lessons of history in thinking tactically and aesthetically about political participatory processes, as surveillance, suppression and brutality are reaching unprecedented levels in America as everywhere else. One singer who got his start in the 1930s knows first-hand the impact of radically creative and contextually subversive sound: as Pete Seeger says in a recent interview,

Let’s find the magic of the right song at the right place at the right time. Musicians can teach the politicians; it’s fun to swap the lead. Musicians can teach the planners: plan for improvisation. Our greatest songs are yet unsung (Wright 2010, p.28-30).

Footnotes

- A term describing participatory artworks focused on the social field was first introduced and used by Nicolas Bourriaud (2002). [↩]

- For a full list see (Friedman 1979). For the theatre companies Artef, Prolet-buehne, Hungarian Workers Shock Brigade among others see (Reynolds, 1986). [↩]

- The New York agitprop theatre companies, Workers Laboratory Theatre and the German language Prolet-Bühne, together founded the loosely organised collective League of Workers Theatres in 1932. The Shock Troupe was an outcropping of the Workers Laboratory Theatre who formed in New York after the Wall Street crash in 1929 and were active until 1934. The group of thirteen core performers lived collectively so that they would be always on call to perform agitprop at factory gates, street corners, rallies and strikes at a moment’s notice (Shteir 1997). By 1934 the League of Workers Theatres grew to include four hundred worker’s theatre companies in cities all over the USA. With the advent of Roosevelt’s Federal Theatre Project, the League changed its name to the New Theatre League (Cosgrove 1985a). [↩]

- The Stanislavski technique involved vividly imagining all the details of a dramatic situation and setting, and thereby empathically entering the feelings of a particular character. Certain questions were meant to greatly attune the empathic abilities of an actor to the feelings of a character in that scenario (Levine I.A. 1980). [↩]

- The play caused uproar not only at the premier in New York on January 5th, 1935, but also most notably on January 15th, 1936 in Seattle and in 1938, Newark, New Jersey (Hyman 1997). In Seattle and Newark the police shut down the play. [↩]

- Hallie Flanagan, the director of the FTP and originator of the Living Newspaper Unit concept, was inspired to do so by her interviews with Meyerhold and her exposure to the Living Newspapers of the Blue Blouses during her trip to the Soviet Union (Mally 2008). [↩]

- Sit-down strikes were ruled illegal in 1939. The Taft-Hartley Act (1947) further prohibited union freedoms and banned Communist Party members from all unions, among other provisions [↩]

- One such strike was the 1937 Woolworth strike in Union Sq. Manhattan. See (Frank 2001) and (Laborarts.org). [↩]

- In the bibliography see: Birdsall 2012; Goodman 2010; Attali 1985; Denning 1997; Lenthall 2007; Lovell 2011; Roscigno and Danaher 2004,; Suisman and Strasser eds. 2011. [↩]

- ‘Sound car’ is how the strikers themselves referred to the vehicle (Fuoss 1997, Fine 1969, Hyman 1997, Kraus 1993, Grey 1979, Zwerin 1993). [↩]

- Speakers were also used on trucks in the Youngstown strike of 1937. (YouTube: Gropper Visits Youngstown) [↩]

- Here the “bulls” are a reference to the police. [↩]

- In ‘With Babies and Banners’ , the sound car is both audible and visible at 29:48. (Grey, 1979). [↩]

- For an incidence of striker’s actions spontaneously being directed on the radio by labour leaders, see (Roscigno, V. J. and W. F. Danaher 2004). [↩]

- By 1940, when the major networks were beginning to monopolise the airwaves, eighty percent of news reports still came from local stations, of which there were four times as many than national stations (Douglas 1999). [↩]

- This figure rose to thirty percent by 1940 (Stamm 2010). [↩]

- Acousmatic music was a term invented in 1955 by Pierre Schaeffer to describe music where one is without the usual reference of seeing its source (specifically tape music played back through loudspeakers.) It was a reference to the pupils of Pythagoras who had their lessons taught to them while he was hidden from view behind a screen. [↩]

- As industrial plants geared up for war in 1939, playing music over the factory loudspeakers became a growing trend. Studies demonstrating the positive effects of music to factory productivity were adhered to, thanks in part to various companies including RCA Victor and the Muzak company (Benson 1945). [↩]

- The Old Testament God regularly appears as an acousmatic voice- but this is a trait he shares with many other deities…The voice…because it cannot be located, seems to emanate from anywhere, everywhere; it gains omnipotence” (Dolar, 2006). [↩]

- Radio was often imitated in the Federal Theatre Project. The sound engineer Leslie Phillips, in a report about sound production by the FTP uses It Can’t Happen Here as an example, describing how the play required, “an imitation radio that actually broadcast from a mythical loudspeaker in the set on stage” (Phillips ca. 1938, p.2). A special switch was built into the turntable to feed the speaker in the radio. As well as “being able to introduce ‘imitation’ static…When the person in question operated the imitation radio on stage, the switch actually closed the circuit from the mixing panel backstage, thus giving the illusion that the actor himself was turning off the radio program” (Phillips ca. 1938, p.2). [↩]

- Loudspeakers in Factories in 1937 would normally be used for announcements, pages and emergency notifications (Benson 1945). Doron notes that in factories, “[sound system] technicians go into plants first and analyse the prevailing noises there, working in terms of decibels…music can be heard clearly [on the plant loudspeakers over the machines] at noise levels up to 100 db.” (1943, p.276). [↩]

- Accordion could have taken over the role of string bass in the sit-downer’s orchestra. (Wikipedia: Blue Grass Bands). [↩]

- Harmonica ensemble was an established popular grouping that began developing in the mid-twenties with the famous Borrah Minevitch and the Harmonica Rascals. (Cullen 2007) Harmonica ensemble was also often combined with theatrical stage antics. The time between the two world wars was known as “the golden age of the mouth organ in America” (Bookrags: Harmonica Bands). [↩]

- There was plenty of theatre in Detroit even before these two theatrical manifestations of the ’37 sit-down strike. In fact, Detroit was particularly distinguished among national cities for its worker’s theatre. At the founding meeting of the United Automobile Workers of which two men, Merlin Bishop and Roy Reuther, who had studied at Brookwood Labour College in New York made sure that a certain amount of union dues went to education and formed classes, drama activities, music groups and sports teams. Bishop was quoted as saying, “labour dramatics are a fundamental part of any workers’ education program.” (Fuoss 1996, p. 125). [↩]

References

Adams, F., 1975. Unearthing Seeds of Fire. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair.

Altenbaugh, R. J., 1980. Forming the structure of a new society within the shell of the old: A study of three labour colleges and their contributions to the American labour movement. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh.

Arent, A., 1938. Forward to One-Third of a Nation. In: Arent, A. One-Third of a Nation. Library of Congress.

Arnheim, R., 1936. Radio: An Art of Sound. London: Faber and Faber.

Attali, J., 2009. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. University of Minnesota Press.

Benson, B. E., 1945. Music and Sound Systems in Industry. MacGraw Hill.

Birdsall, C., 2012. Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology and Urban Space in Germany, 1933-1945. Amsterdam University Press.

Bookrags. Harmonica Bands. Available from: http://www.bookrags.com/research/harmonica-bands-sjpc-02/ [02/08/13].

Bourriaud, N., 2002. Relational Aesthetics. Les presses du reel.

Burris-Meyer, H., Interview transcript by Brown, L., 1977 Research Centre for the Federal Theatre Project, Oral Histories. George Mason University.

Chaplin, C. 1936. Modern Times. Janus Films/Criterion. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wUYRah5jLl8

Clark, K., 1929. Music in Industry. National Bureau for the Advancement of Music.

Cohen, R. D., 2010. Work and Sing. Crockett, California: Carquinez Press.

Cosgrove, S., 1985a. From Shock Troupe to Group Theatre. In: Samuel, R., E. MacColl and S. Cosgrove, eds. Theatres of the Left 1880-1935: Workers’ Theatre Movements in Britain and America. London: Routledge Kegan & Paul.

Cowell, H., 1931. Music of and for the Records. Modern Music 8 (3), 34.

Cullen, F., F. Hackman and D. McNeilly., 2007. Vaudeville, Old and New: an encyclopedia of variety performers in America. New York: Routledge.

Denning, M., 1997. The Cultural Front: The Labouring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. London: Verso.

De Rohan, P., 1938b. First Federal Summer Theatre: A Report. Federal Theatre Project. Curtis Theatre Collection. University of Pittsburgh Hillman Library.

Dolar, M., 2006. A Voice and Nothing More. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Doron, A. K., July 1943. Music in Industry. The Musical Quarterly. 29(3), 275-290.

Douglas, S. J., 2004. Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination. University of Minnesota Press.

Durham, M. and J. Handler, A. Racusin, and N. Simonian. Charlie Chaplin and Silent Films: Modern Times. Available from: http://transcriptions.english.ucsb.edu/archive/topics/infoart/chaplin/moderntimes.htm [August 2, 2013].

Federal Theatre Project Technical Studies File, 1935-1939. Box 133 Living Newspaper, Sound Material. Library of Congress.

Federal Theatre Bulletin, Vol. 1 No. 6. 1936. Federal Theatre Project. Curtis Theatre Collection. University of Pittsburgh Hillman Library.

Fine, S., 1969. Sit-Down: The General Motors Strike of 1936-1937. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Flanagan, H., 1938a. Summary of Federal Theatre Activities to September 1938. Federal Theatre Project. Curtis Theatre Collection. University of Pittsburgh Hillman Library.

Frank, D., 2001. Girl Strikers Occupy Chain Store, Win Big. In: Kelley, R. D. G., D. Frank and H. Zinn. Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labour’s Last Century. Boston: Beacon Press. 59-118.

Friedman, D., 1979. The Prolet-Buehne: America’s First Agit-Prop Theatre. Thesis (PhD). University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Friedman, D., 1985a. A Brief Description of the Workers’ Theatre Movement of the Thirties. In: McConachie, B. A. and D. Friedman, eds. Theatre for Working-Class Audiences in the United States, 1830-1980. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. 111-120.

Fuoss, K. W., 1997. Striking Performances: Performing Strikes. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Goodman, D., 2011. Distracted Listening: On Not Making Sound Choices in the 1930s. In: Suisman, D. and S. Strasser eds. Sound in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. University of Pennsylvania Press. 15-46.

Goodman, S., 2010. Sonic Warfare. MIT Press.

Grey, L., 1979. With Babies and Banners: Story of the Women’s Emergency Brigade. New Day Films. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pa75V-tdBko [August 2, 2013].

HistoricalVoices.org. Larry Jones describes the meeting between Lewis and Murphy on February 9. Available from: http://www.historicalvoices.org/flint/embed.php?text=jones_larry_06-09-78A1ds_edited2.rt&audio=flint-a0a0e4-a.rm&speaker=Larry Jones [August 2, 2013].

Hyman, C. A., 1997. Staging Strikes. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Jarvis, A., 1994. The Living Newspaper in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania History. 61(3), 332-355.

Labourarts.org. 1937, New York, Occupation: Retail and wholesale – department stores, grocery stores, warehouses. Available from: http://www.labourarts.org/collections/item.cfm?itemid=61 [August 2, 2013].

Leclau, E. and C. Mouffe., 1985, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

Lefebvre, H., 1992. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Continuum.

Lenthall, B., 2007. Radio’s America: The Great Depression and the Rise of Modern Mass Culture. University of Chicago Press.

Levine, I. A., 1980. Left-Wing Dramatic Theory in the American Theatre. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press.

Library of Congress. Federal Theatre Project, Sound Department - Report - Installations, Difficulties, Various Productions Named - Philips, Leslie. Available from: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=ftscript&fileName=fpraf/09670024/ftscript.db&recNum=0) [August 2, 2013].

Lichtenstein, N., 1995. Walter Reuther: The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit. Basic Books.

Lovell. S., Summer 2011. How Russia Learned to Listen: Radio and the Making of Soviet Culture. Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 12(3), 591-615.

Kraus, H., 1993. Heroes of Unwritten Story: The UAW, 1934-39. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Mally, L. 2008. The Americanisation of the Soviet Living Newspaper. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies.

Marxists.org. Striking Flint. Available from: http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/amersocialist/genora.htm [August 2, 2013].

Mouffe, C., 2000. The Democratic Paradox. London: Verso.

Phillips, L., ca.1938. Synopsis of Sound Installations in Federal Theatres. Difficulties Encountered and Overcome, Technical Explanations. Music Division, Federal Theatre Project, Living Newspapers, Box 967, Folder 25. Library of Congress.

Raymond, T. K., 2009. Labour, performance, and theatre: Strike culture and the emergence of organised labour in the 1930’s. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southern California.

Reuss, R. A. with J. C. Reuss., 2000. American Folk Music and Left-Wing Politics, 1927-1957. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press.

Reynolds, R.C., 1986. Stage Left. Troy, New York: Whitston Publishing.

Romer, C., 1986. Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data, The Journal of Political Economy. 94(1), 1-37

Roscigno, V. J. and W. F. Danaher., 2004 The Voice of Southern Labour: Radio, Music, and Textile Strikes, 1929-1934. University of Minnesota Press.

Samuel, R., 1985b. Waiting for Lefty: Introductory Note. In: Samuel, R., E. MacColl and S. Cosgrove, eds. Theatres of the Left 1880-1935: Workers’ Theatre Movements in Britain and America. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Schafer, R. M., 1976. The Tuning of the World. Alfred A. Knopf.

Shogan, Robert., December 2006. Labour Strikes Back. American History. 36-43.

Shteir, R., July, 1997. Workers Laboratory Theatre. The Nation. 265(2), 32.

Sporn, P., 1985b. Working Class Theatre on the Auto Picket Line. In: McConachie, B. A. and D. Friedman, eds. Theatre for Working-Class Audiences in the United States 1830-1980. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. 155-170.

Stamm, M., 2011. The Sound of Print: Newspapers and the Public Promotion of Early Radio Broadcasting in the United States. In: Suisman, D. and S. Strasser eds. Sound in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. University of Pennsylvania Press. 221-242.

The Great Depression in Washington State. The Power of Art and the Fear of Labour: Seattle’s Production of Waiting for Lefty. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/depress/seattle_waiting_for_lefty.shtml [August 2, 2013].

The Manhattan Chorus. “Sit Down.” recorded April 28, 1937. In Ronald D. Cohen Songs For Political Action, Bear Family Records BCD 15 720, 1996.

Thompson, E., 2002. The Soundscape of Modernity. The MIT Press.

Thompson, E., 2009. Remix Redux: In the Silent Film Era, the Roots of the DJ. Cabinet Magazine. Issue 35, Fall 2009. Available from: http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/35/thompson.php [April 10, 2012].

U-S-history.com. Unemployment Statistics during the Great Depression. Available from: http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1528.html [August 2, 2013]

Watson, Morris., ca. 1937. Writing the Living Newspaper. Music Division, Federal Theatre Project, Living Newspapers, Box 133, Folder 25.8. Library of Congress.

Wikipedia. Bluegrass Music. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluegrass_music [August 2, 2013]

Wikipedia. Method Acting. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Method_acting [August 2, 2013].

Wikipedia. The Shadow. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Shadow [August 2, 2013]

Wright, S., November 2010. Pete Seeger: If I Had A Song: an Icon of American Music Goes Back to School – and Grants an Exclusive Interview. Teaching Music, 28-30.

YouTube. Flint Sitdown Strike – Pt. 1. (excerpt from the PBS American Experience Video “Sit Down and Fight.”) Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aLUNW4zoPQ [August 2, 2013].

YouTube. Gene Autry performs ‘The Martins and the Coys’ in ‘The Big Show’ (1936). Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BqqTq18K25Q [August 2, 2013]

YouTube. Gropper Visits Youngstown. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UhAqhwYdoN0&feature=player_embedded - at=261 [August 2, 2013].

Yu, L., November 2005. The Great Communicator: How FDR’s Radio Speeches Shaped American History. The History Teacher. 39(1), 89-106.

Zwerin, C., 1993. Sit Down and Fight. The American Experience. PBS Video.

AcknowledgementsDedicated to the memory of Toshi Seeger, 1922 – 2013. Many thanks to the editor for her commitment to this article.

Bio

Jeremy Woodruff is currently a Mellon pre-doctoral scholar in Composition and Theory at the University of Pittsburgh. His dissertation is entitled Sound Art and the People’s Microphone: Towards a Music Theory of Resistance. He studied composition at the Royal Academy in London with Michael Finnissy from 1999 – 2001 and Ethnomusicology at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam 2002 - 2004. Since 2007 he is lecturer in composition and music theory at the Neue Musikschule in Berlin, Germany where he is also director. His writings are published by Errant Bodies Press and Klangzeitort (Berlin) and compositions published by Neue Musik Verlag, Berlin. For more information visit: www.jeremywoodruffmusic.com.