A Window in Between: Mediation Strategies in Networked Sonic Arts

By Felipe Hickmann & Rui Chaves

Abstract

Whilst allowing for the establishment of novel performance practices, the availability of audio and video networking technologies poses questions regarding the representation of remote bodies, spaces and actions. Awareness of the formal attributes of the medium can greatly contribute to the development of successful presentation strategies, particularly as their design is incorporated into the broader creative process of a piece. We borrow from the concept of network dramaturgies to help illustrate this compositional approach, and suggest that the use of conceptual metaphors – particularly that of a network window – can lead to meaningful dialogues between the work and the medium.

Keywords

network music, sonic art, mediation, performance, dramaturgy

Introduction

The practice of music and sonic arts over computer networks has been approached from a number of different directions in recent years, partially as a result of the growing availability of the Internet as a prolific and widespread medium. While pioneering initiatives were restricted to early networking infrastructure (e.g. Max Neuhaus’ collaborative works using telephone landlines in the 1960s), current works build on the potentials of pervasive computing, locative media and high-speed connectivity for establishing links between remote spaces. Analyses of these initiatives have looked into their social (Tanzi, 2000; Schroeder & Rebelo, 2009), aesthetic (Ascott, 2003; Kane, 2007) and technical aspects (Carôt, 2009; Renaud, 2009), and have often run parallel to the creative process of composers and artists.

Network performance initiatives often aim at creating seamless real-time audio-visual connections between distant sites and performers. Despite important technological advancements, a number of conditions interfere with this process. The simple presence of a technological setup linking two or more remote places, regardless of the actual distance between them or their cultural and social contexts, raises a fundamental question: how to present a local rendering of remote bodies, spaces and actions in a way that is both meaningful to the audience and relevant to the artwork?

Two recent works may provide informative examples. Rob King’s and Pierre Proske’s piece Packet Loss (2010) comprises two pianos connected over the Internet. One of them features a live improviser, while the other – a Yamaha Disklavier – responds automatically to the remote improvisation. Only exceptionally loud musical gestures from the live performer are acknowledged and reacted upon by the Disklavier, defining a performance setting where communication is dependant on physical effort. The network, as described by the authors, becomes a “graveyard of lost packets and data that didn’t make it” (King & Proske, 2010). The local rendering of the remote performer ignores all aspects of his physical presence, focusing instead on his action as filtered by the medium.

King & Proske’s Packet Loss (excerpt).

Justin Yang’s Webwork I (2010) relies on a carefully designed presentation strategy that highlights agency and ensemble play rather than the emulation of remote spaces. The piece presents improvisers with a live-generated projection of a clock-like object, which features three moving hands representing particular players in three dislocated ensembles. As each hand crosses a variety of symbols dynamically generated during the performance, the corresponding players improvise in response. Audiences are tacitly encouraged to decode the system, slowly connecting the visual information to specific agents and actions.

Justin Yang’s Webwork I (excerpt).

These initiatives share a remarkable awareness of the formal attributes of the medium they operate in, exploring, respectively, attributes of data circulation and distributed collaboration over computer networks. The concern to build dialogues between performance practice and the ontology of the medium is widespread in telematic artworks; it is reflected for example in Gollo Follmer’s well-known definition of network music – the one where “the specifics of electronic networks leave considerable traces” (Föllmer 2005, p.185). For Föllmer, network music goes beyond the practical matters of facilitating performance over long distances, bringing the medium to the centre of the artwork. That position is corroborated by other scholars such as Roy Ascott (2003) and Steve Dixon (2007), whose accounts of telematic art and network performance highlight the creative potential of mediation. This potential is often expressed through poetics of disruption and interference between visual and sonic representations of body, place and time. The manipulation of network topology and spatial relationships between remote sites may inform the design of particular presentation frameworks, which will in their turn play a central role in the process of devising a piece of network music.1

The levels of interdependence between the work and its presentation strategies have already been noted by Pedro Rebelo (2009) and Franziska Schroeder (2009), who recall the concept of dramaturgy to help shed light on the specifics of networks as places for performance. Dramaturgy relates to the composition of the performance space in all its components; systematically described in the 18th century by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, the discipline concerns the range of choices entailed in the presentation of a dramatic work. In the context of network performance, dramaturgies can help address issues of authorship, collaboration, technology and space, thus highlighting “the need for very specific design concepts of a performance environment, particularly in the initial stages of a work’s development” (Schroeder 2009, p.383). The configuration of a certain network topology, for example, can work in conjunction with other scenic elements under the overarching direction of a particular dramaturgy; that concept is discussed below as related to the notion of “network window”, and illustrated by two network music pieces: A man, a Mark, Amen (2010) and Paulista (2011).

Discussion

A window in between

George Lakoff, in a series of works following his influential Metaphors We Live By, has demonstrated the widespread and often unnoticed use of conceptual metaphors in everyday speech. His study of conceptual metaphors will help illustrate our use of the window metaphor in network performance contexts.

For Lakoff & Johnson (2003), a conceptual metaphor takes place whenever we attempt to understand an idea by resorting to the conceptual domain of another idea (“argument is war” (p.4) and “time is money” (p.7) are common examples they proffer). The two domains at play are called target and source domains. The target domain relates to the immediate matter at hand, while the source domain is the one “in which important metaphorical reasoning takes place and that provides the source concepts used in that reasoning” (Lakoff & Johnson 2003, p.265).

Conceptual metaphors may help contextualise network music performance as a novel form of performance practice. Resorting to metaphors is not an unprecedented strategy for tackling a new medium; the popularisation of personal computers was accompanied by the desktop metaphor, which allowed users to interact with an organisation system with which they were already familiar (Mountford 1995). The complex fabric of network servers and connections that forms the Internet is largely understood through the metaphors of ‘web’ and more recently ‘cloud’ (Erdogmus 2009).2

As a new practice, taking place in an essentially flexible medium and whose conventions for play are not fully established, network music can resort to varied source domains both as creative inspiration and as a means to address issues of representation, communication and engagement between players. The absence of conventional improvisational and performance cues such as shared pulse, breath and eye contact, for example, can be reframed under metaphors of virtuality, error and disturbance in the communication channel, as explored in King & Proske’s Packet Loss. Emily Robertson’s Microcosmic Theory of a Stroll (2011) guides improvisers through an imaginary path that visits markets, restaurants and cabarets; the scenarios depicted in the score provide players with colourful references from which to construct musical dialogues, largely bypassing the need for other cues for collective play.

Emily Robertson’s Microcosmic Theory of a Stroll (section).

In order to better understand the role of mediation in network music performance, we will resort to the source domain of a ‘window’. The New Oxford American Dictionary (McKean 2005) defines window as “an opening in the wall or roof of a building or vehicle that is fitted with glass or other transparent material in a frame to admit light or air and allow people to see out”. While the definition seems rather narrow in its account of the functions and formal attributes of a window, it makes clear that one of its purposes is to act as an interface between spaces. The window is selective as to what it lets through – typically light or air – while its size and position may enable the passage of objects or even people. A window has a shape and is fitted with a specific material – which can range from fully transparent to fully opaque. It is a dynamic object, meaning it can be found in different states along any stretch of time: closed, open or any condition in between. All these attributes affect the ways in which spaces are perceived across the medium – that is, the particular impression a space makes on observers at the other side.

The window metaphor has been applied to numerous different target domains. Common speech immediately suggests a few of them: “window of opportunity”, “window of vulnerability” and “windows of the soul” are expressions that refer to different attributes of the source domain in order to clarify aspects of phenomena that reside on distinct realms – time frames for action and organs of the sense, for example. Assuming network performance as the target domain for the present metaphor, we realise that every network connection links at least two nodes. It also imposes its own set of restrictions regarding what can or cannot be transmitted, since the capture, transmission and reproduction devices are necessarily limited. While this analogy may prove functional for the analysis of varied forms of communication mediated by technology, we propose a focus on the creative potential of the window metaphor in the particular context of network performance.

Here the notion of dramaturgy plays a crucial role, as choices have to be made regarding what (and how) content will be presented, and which aspects of the remote space will be left behind. The conceptual domain of the window helps delineate fitting dramaturgies for network performance, informing the design of physical spaces, network topologies and modes of interaction.

An introductory relationship between physical and networked windows may be identified in the writing of Julian Rohrhuber (2007). Rohrhuber describes network music as playing on the balance between levels of transparency and opacity afforded by specific technological frameworks. Mediation thus produces a decisive impact on the outcomes of these performances: the medium may be treated as virtually invisible (“transparent”) as the result of seamless connections between sites, or fully apparent (“opaque”) whenever its features and limitations are subsumed under the dramaturgy of the work (pp.142-144). Schroeder & Rebelo (2009) take a similar direction in acknowledging the fragmentary character of the network, challenging popular ideas of all-embracing connectedness and highlighting the performative qualities of the process of mediation, one where the body itself may be seen as a welcome “disturbant”.

The following analyses will look at the dramaturgy of network music from three different angles. The problems of visual and aural presentation of remote spaces and players are condensed under the term ‘framing’. That comprises issues such as the scale, orientation, position, size and distance of sources, as captured at one end of the connection and rendered at the other end. This definition of framing relates to similar properties of the correlating window metaphor: in both cases the medium imposes a specific profile for the presentation of the other side.

Problems of topology, on the other hand, concern the distribution of information between sites – that is, the patterns establishing how and when data circulates among the network nodes. They relate to the regulating aspect of the source domain: the window, acting as an interface, is able to mediate different levels of access and communication between the local and the remote.

Finally, the matters of synchronicity encompass the overall uniformity and consistency of the audio-visual link, which may be affected both by network latency and by non-linear strategies in correlating sound and image. Here the window metaphor encounters a possible breakdown; in a purely denotative sense, a window lacks flexibility to account for much of the instability and unpredictability imposed by network connections. The potential reach of the metaphor, with its possibilities and limitations, will be further explored through the analyses that follow.

A man, a Mark, Amen

A man, a Mark, Amen, by Felipe Hickmann with text by Caetano Galindo, was one of the pieces premiered at the Co-Me-Di-A showcase concert, which involved musicians in Belfast, Graz and Hamburg, in November 2010. It was designed with the specific technical framework of that concert in mind; each side of the stage was fitted with video screens and loudspeakers, which displayed players at each of the remote venues.

Stage setup of the Co-Me-Di-A a showcase concert. Photo by Caroline Forbes.

A man, a Mark, Amen illustrates how the creative process of a piece can be shaped by the affordances of a particular performance setting. Aspects of visual presentation and network topology entailed in the Co-Me-Di-A Showcase inspired a dramaturgy that actively interfered with the flow of performance information between dislocated players and audiences. Each of the three concert halls featured a small ensemble and a local audience, who were able to experience remote play through screens and loudspeakers, as if windows existed at both sides of the stage, allowing them to see and hear action in distant places. That link, however, was often interrupted, leaving participants to wonder about the course of the performance at the other venues. The piece builds on a poetics of secrecy and concealment, stimulating a variety of readings that develop independently in each space.

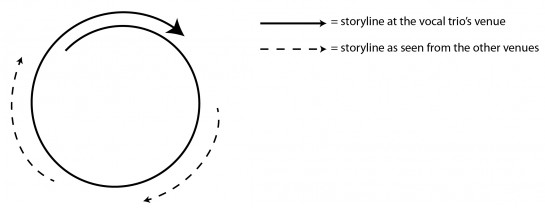

A man, a Mark, Amen: Network windows are initially closed, but later open to reveal the performance at remote locations.

The window metaphor acted as a conceptual model for the design of this particular dramaturgy. Windows are normally described in terms of what they let through, but their function is as much one of concealing as it is one of revealing. The choice for a particular position, shape or material implies the renunciation of countless alternative points of view; bathroom windows, for example, are often designed to let luminosity through while obscuring contrast and sharpness. The metaphorical windows of A man, a Mark, Amen fulfill a similar role: they are responsible for moderating how much information is allowed into remote sites, thus affecting the narrative plan underlying the piece. One of the venues features a vocal trio, who narrates the circular tale of a writer who creates a designer who draws an actress who enacts the initial writer; the chain of events is thus virtually endless, setting up a formal backdrop for explorations in the themes of fantasy and deceit. The local audience in that venue is the only one to follow all stages of the narrative; since windows ‘open’ and ‘close’ several times during the performance, the other two sites only get to experience fragments of the story, shattered into pieces and often out of sequence.

A man, a Mark, Amen: Varying topology modes as windows open and close between venues.

A man, a Mark, Amen: Narrative cycle as performed by the vocal trio, fragmented and distributed across remaining sites by a roulette-like system enacted by network windows.

The network topology stemming from that process is distinctly asymmetric. Audiences in each of the venues experience different renderings of the same work, resulting from the particular behaviour of their respective network windows. Coordination between musicians and the sense of a shared event are accomplished not by revealing remote performances in increasing detail, but by concealing aspects of the remote action according to a strategy established beforehand.

The disruption in the audiovisual synchronicity is another key element in A man, a Mark, Amen. While sound is blocked and released several times during the performance, video content is streamed without interruptions. Audience members have informally reported questioning the technical infrastructure at first, but eventually wondering about the action at the remote sites, which they could always see, but only sometimes hear. That effect was further enhanced by the theatrical character of the vocal trio, whose score suggested gestures such as “gasp (scared or surprised)” and “stumble (looking anxious)”.

A man, a Mark, Amen: singers enact a dramatic passage of the score.

Musical interactions were also frequently affected by the behaviour of network windows. Two sections of the piece rely on chains of imitative processes that repeatedly cross the distance between spaces, connecting actions by players to reactions by remote counterparts; the opening and closing of network windows is responsible for regulating the establishment and duration of these processes. Musicians are also instructed to react to particular words voiced by singers, but these directions can only be fulfilled whenever windows are opened and the narrative stream – much like wind coming from the outside – ‘blows’ into the venues where instrumental ensembles are located.

A man, a Mark, Amen thus illustrates the application of metaphors to the design of wider dramaturgies, borrowing from a source domain in order to delineate musical interactions, network topology and narrative plan. In doing so, the piece highlights a key feature of all forms of mediation that is often neglected in network performance: the possibility to construct discourses by restraining and regulating the flow of performance information rather than providing increasingly realistic renditions of remote spaces.

A man, a Mark, Amen as seen from the Sonic Arts Research Centre, Belfast.

2.3 Paulista

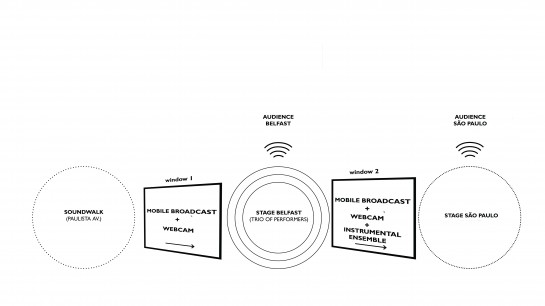

Paulista, by Rui Chaves and Felipe Hickmann, is a network music piece for three musicians and a remote sonic artist. In its first performance in May 2011, the piece connected the Sonic Arts Research Centre in Belfast; Paulista Avenue in São Paulo; and the Laboratory of Acoustics and Computing (LAMI) of the University of São Paulo. Local musicians and the remote sonic artist assume rather different roles in the piece. The networked performer carries out a soundwalk at Paulista Avenue, and broadcasts live audio from his path using Liveshout, a custom-developed iPhone application. This broadcast is fed into the concert hall in Belfast, where the trio of musicians react to the sound of the urban landscape. A video screen above the musicians completes the scenario, showing images captured live from the avenue by the Internet portal EarthCam.3

Paulista: Musicians in Belfast and a section of Paulista Avenue in the video projection.

The dramaturgy of Paulista is particularly concerned with delineating a specific network topology for the concert. Each of the three sites retains a specific status in the formal layout of the piece, leading to extensively asymmetric patterns of presentation. There is no audience in Paulista Avenue, and no performance information is ever transmitted there. The performer, focused on carrying out his lonely exploration of that space, has no feedback whatsoever of the musical consequences of his actions at the other two venues.

Paulista: Network topology.

Unlike the network topology described in A man, a Mark, Amen, in Paulista all network links are unidirectional, meaning that audio and video feeds are broadcast from one space into the next, without any of those feeds taking the return path. After the first step of audio transmission is completed between Paulista Avenue and Belfast, the soundwalk is joined by the trio of musicians and transmitted back to a separate location in São Paulo, this time into a concert hall in LAMI, inside the University of São Paulo. Because of this particular configuration, Belfast assumes a regulating function in the piece, acting as a control node that filters and transforms the original content of the soundwalk before passing it ahead. Improvisers follow a script in which transient aspects of the soundscape in Paulista Avenue initiate specific musical reactions. Both local and remote sounds then feed a convolution filter4 before the output is transmitted to LAMI. Back in São Paulo, the local spectators are presented with an unusual rendering of a space that is an ordinary part of their lives, now transformed by the active mediation of a remote space.

The topology of Paulista can be described as a series of three separate spaces linked by two glass windows. These windows have the attribute of only letting image and sound through in a single direction – a configuration achievable through the use of tinting films of the type used in official vehicles and police interrogation rooms. Thanks to the particular one-way orientation afforded by the piece’s successive network windows, each space experiences a different presentation layer of a single work.

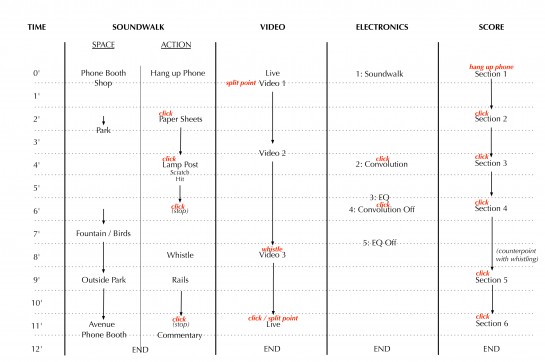

The matters of synchronicity and framing in Paulista become apparent when the video projection comes into play. Since the webcam was provided by a 3rd party and could not be moved, a great deal of the soundwalk was scripted taking into consideration the position of the performer in relation to a fixed video frame – a virtual window looking down at a limited section of the street. The performer’s entrance and departure in and out of the screen was part of a wider dramaturgy that also prescribed his path and actions, the content and timing of the musicians’ scores, a layer of live sound processing and the triggering of pre-recorded video clips.

Paulista: Master script showing directions followed by the sonic artist (left column), live video and audio processing, and musicians onstage (next columns to the right).

The availability of video footage of the same webcam, recorded at different moments of the day and featuring the performer in varied choreographic moves, allowed for an exploration of the concepts of liveness and synchronicity in Paulista. Since live and recorded footage often alternated on the screen, the audience was left to wonder about the true location and status of the performer. Sound and moving image would sometimes seem synchronous and sometimes completely detached, while a musical discourse was built on top of this audiovisual interplay, playing on spatial and temporal continuity, and prompting debates about authenticity and deception. The window metaphor was made to account for occasional glimpses into the past, in a deliberate elaboration on the formal attributes of the source domain with important consequences on the extent and design of the metaphor.

Paulista as seen from the Sonic Arts Research Centre, Belfast.

Conclusion

Mediation via computer networks has brought about an entirely new range of technical circumstances for performance, engendering a fresh creative domain for composers and sound artists to explore. Approaching the composition of network music through the design of unique dramaturgies for performance may help address and make creative use of the particularities of the medium, a process that can be guided at a conceptual level by the use of metaphors. By borrowing ideas and formal parameters from separate domains, we may expand our understanding of the medium and engender innovative forms to tackle its resources and limitations.

It must be noted, however, that the window metaphor cannot account for every single aspect of the target domain. Windows are attached to buildings; they are finished objects that do not usually lend themselves to easy structural intervention. The dramaturgy of a network music piece, on the other hand, can stretch the limits of the source domain and create imaginary windows, objects that – while retaining some of their defining features – are able to dynamically change position, shape, size and focus, among other attributes.

The network affords a level of unpredictability and adaptability that the concept of a physical window struggles to describe. Such limitations, however, do not invalidate the metaphor. Lakoff and Johnson (2003, p.254) observe that conceptual mappings tend to be partial, and as a result “a source domain element is not mapped if it would produce an inference that would contradict the internal structure of the target”. That is the case when issues of synchronicity come to play in Paulista and A man, a Mark, Amen. Both pieces occasionally build on levels of audiovisual discontinuity; the structure and functionality of a physical window has little to contribute to the design of these particular features in these works.

The notions of synchronicity, topology and framing are also evidently borrowed from different domains – particularly computer science and media studies – and their use to describe network relationships in a performance context relies on more or less established conceptual metaphors.5 The use of such metaphors is justified to the extent that they help to frame network music as a practice that ties into everyday lived experience. The reality of imperfect or fragmented representation is manifest not only in the flaws of technology (lack of network coverage, highly compressed data on VoIP software) but also whenever different political, social and cultural contexts come into contact. The acknowledgement of such limitations is an important aspect of the creative process in network music and may inform the design of presentation frameworks that successfully render the medium.

Footnotes

- The creative potential of mediation can also manifest itself through reflexivity and meta-narratives – for example in the use of glitch in electronic music, or in practices that incorporate network artefacts such as jitter and latency to the aesthetics of the artwork. In this article, however, we focus on mediation as the exchange of performance information across dislocated spaces; the creative potential, in this case, is latent in the flexible configuration of medium, spaces and strategies for presentation and communication. [↩]

- It is illustrative to note how, while referring to the same target domain – a physical distribution of network nodes – each of these metaphors highlights a different subset of its attributes and potentials; ‘web’ refers to the physical arrangement of network nodes, underlining qualities of complexity and interconnectivity, while ‘cloud’ suggests ubiquity, intangibility and formal unpredictability. [↩]

- http://www.earthcam.com/cams/brazil/saopaulo/ [↩]

- In digital audio processing, convolution is an operation in which two waveforms are multiplied by each other, resulting in a third waveform that retains timbral qualities from both sources. [↩]

- “Synchronicity” was first coined as a philosophical concept by Carl Jung in the 1920s (Tarnas 2006); “topology” is a well-established field of study in mathematics, con-cerned with fundamental properties of space (McKean 2005); “framing” appears in social sciences and visual arts indicating deliberate focus on particular angles of a subject matter. (Benford & Snow, 2000; Herbener et al, 1979). [↩]

References

Ascott, R., 2003. Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Benford, R. & Snow, D., 2000. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. In Annual Review of Sociology, 26, pp.611-639.

Carôt, A., 2009. Musical Telepresence: A Comprehensive Analysis Towards New Cognitive and Technical Approaches. Thesis (PhD). Universität zu Lübeck.

Dixon, S., 2007. Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance Art, and Installation. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

Erdogmus, H., 2009. Cloud Computing: Does Nirvana Hide Behind the Nebula? In IEEE Software, 26, pp.4-6.

Föllmer, G., 2005. Electronic, Aesthetic and Social Factors in Net Music. In Organised Sound, 10(03), pp.185-192.

Herbener, G., Tubergen, N.V., Whitlow, S., 1979. Dynamics of the Frame in Visual Composition. In Educational Technology Research and Development, 27(2), pp.83-88.

Kane, B., 2007. Aesthetic Problems of Net Music. In Spark Proceedings. Minneapolis. Available from: http://www.browsebriankane.com/My_Homepage_Files/documents/Aesthetic_Problems_of_Net_Music.pdf [Accessed 8 May 2013].

King, R. & Proske, P., 2010. Packet Loss: A Solo-Duet for Keyboard, Network, and Disklavier. Composition.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M., 2003. Metaphors We Live By. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McKean, E., 2005. The New Oxford American Dictionary. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Montford, S.J., 1995. Tools and Techniques for Creative Design. In: Baecker, R., ed. Readings in Human-Computer Interaction: Toward the Year 2000. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

Rebelo, P., 2009. Dramaturgy in the Network. In Contemporary Music Review, 28, no. 4(8), pp.387-393.

Rebelo, P., 2009. Dramaturgy in the Network. In Contemporary Music Review, 28(4), pp.387–393.

Renaud, A., 2009. The Network as a Performance Space: Strategies and Applications. Thesis (PhD). Queen’s University Belfast.

Robertson, E., 2011. Microcosmic Theory of a Stroll. Composition.

Rohrhuber, J., 2007. Network Music. In Collins, N., ed. The Cambridge Companion to Electronic Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.140-155.

Schroeder, F., 2009. Dramaturgy as a Model for Geographically Displaced Collaborations: Views from Within and Views from Without. In Contemporary Music Review, 28(4), pp.377–385.

Schroeder, F. & Rebelo, P., 2009. Sounding the Network: The Body as Disturbant. In Leonardo Electronic Almanac, 16(4-5), pp.1–10.

Tanzi, D., 2000. Time, Proximity And Meaning on the Net. In CTheory, pp.1–6. Available from: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=124 [Accessed 8 May 2013].

Tarnas, R., 2006. Cosmos and Psyche. New York: Penguin Group.

Yang, J., 2010. Webwork I. Composition.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the contribution of Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia (www.fctes.mct.pt) towards Rui Chaves’ PhD funding, making this research possible. Further creative work by the authors, exploring the topics of mediation and disloca-tion in networked sonic arts, can be found at http://www.felipehickmann.com and http://www.ruichaves.com/home/works/

Bio

Felipe Hickmann is a Brazilian composer and performer. He holds a multidisciplinary background, ranging from contemporary and popular music to sound design for film, theatre and video games. His work builds on the creative potential of the concepts of absence and secrecy, which he adopts in the development of new dramaturgical approaches for network music performance – the main topic of his PhD research at the Sonic Arts Research Centre, Queen’s University Belfast. Felipe's publication record includes articles in Soundweaving, an upcoming edition on improvisation published by Cambridge Scholars, and in a special issue of Technoetic Arts entitled “Transcultural Tendencies | Transmedial Transactions”. His music has been played in venues worldwide, often stimulating practices of structured improvisation and making creative use of presence and liveness issues. www.felipehickmann.com

Rui Chaves researches and does creative work in the areas of sound art, performance and mobile audio. He has presented his work at ICMC (International Computer Music Conference) and NAISA (New Adventures in Sound Art), having recently collaborated in a large-scale community project in Belfast (“Sounds of the City”). He has published in journals such as Organised Sound and a special edition of Technoetic Arts entitled “Transcultural Tendencies | Transmedial Transactions”. Rui is currently pursuing a PhD at the Sonic Arts Research Centre with funding from Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia. www.ruichaves.com