Evoking the sublime: Absence and presence in live electroacoustic performance

By Guy Harries

Abstract

Live electroacoustic performance juxtaposes two main elements: the real, present and physical, against the simulated and disembodied. The relationship between the two, one of ambiguity, dissonance, or unexplained connections, can create poetic affect. Two such affects will be discussed here: the uncanny and the sublime. Using an interdisciplinary approach, I will explore these themes in the context of ritual and performance traditions as well as critical studies, and will apply them to the electroacoustic case. I will distinguish between several types of ‘absence’: evoked absentees, partial absences and doubles. I will refer to Brook’s ‘holy theatre’, Chion’s ‘acousmêtre’ and Link’s discussion of silence. I will also show how ‘absence’ has been used expressively in the works of Lynch, Dodge, Ostertag, and Crumb as well as my own work.

Keywords:

Electroacoustic; live electronics; dramaturgy; musical performance; sublime; performance theory; audiovisual.

Introduction

There is a sense of duality to electroacoustic performance, manifest in the relationship between the presence of physical entities such as the performer, the performance space and the props, and the more absent, ephemeral quality of the electroacoustic sound. In many cases, some connection is established through gesture, narrative or the context of the performance. However, electroacoustic sound maintains a certain ambiguity: it drifts between embodiment and disembodiment. It refers to other bodies, images, locations or an invisible cause of existence. Discrepancies between the embodied-present entities on stage and the disembodied-absent electroacoustic sound require the audience to negotiate two worlds. The creators of a performance can facilitate the perception of connections within this duality and even use its discrepancies to create poetic affect. In this article I examine two such affects: the uncanny and the sublime. A number of works in which these affects are evoked in a performative context will be discussed. While not all of these works use electroacoustic sound, they can inform the design of performance modes that do.

A main underlying premise of this discussion is that the live electroacoustic mode is a performance discipline, and therefore requires the creation of a dramaturgy. ‘Dramaturgy’ is a term used broadly in the field of performance. Drawing on the framework laid by Aristotleʼs Poetics we can derive some main points of emphasis for a dramaturgical framework such as time, place and action as well as the structure and inner workings of drama and the perspective of the spectators (Schroeder 2009). By using this framework we can focus on the relationships that occur at the moment a work is performed: between the performer and the sounds, between the audience and the performance, and the relationship of the elements of performance to the space in which they take place. Such a dramaturgical approach requires the creation of meaning and affect, addressing the subjectivity of the spectator/listener. By discussing two such affects – the sublime and the uncanny – in the context of live electroacoustic performance, I aim to demonstrate how a dramaturgical framework can provide a methodology that informs the creative process, starting at the initial composition stages, through rehearsal and the actual performance.

Absence and presence in electroacoustic performance

Director David Lynch gives sound and hearing a central role in his work (see Chion 2006, p. 159). A key scene in his film Mulholland Drive (2001) exploits the eerie sensation that arises from the disembodiment of recorded sound. The film’s two young protagonists, Rita and Betty, arrive at the nightclub Silencio. On stage, a musician is playing a jazz tune on the trumpet. After finishing a few musical phrases, the player slickly removes the trumpet from his mouth, but surprisingly the music continues. The charismatic show-master draws our attention to the fact that this is all an illusion, it is “all recorded… it is all a tape”. A singer then enters the stage and sings a heart-rending song. Rita and Betty burst into tears when the singer suddenly collapses, seemingly dead, and is carried away on a stretcher while her voice continues to resound within the space. An ambiguity of absence and presence creates an uncanny atmosphere; rather than feeling that we are being fooled in a ‘fake’ performance, we are mesmerised by this ambiguity. Though this initially seems like a familiar performance situation (a musician on stage playing an instrument or singing), it soon transforms into an unfamiliar, surreal state when we, the audience, realise that what we thought was ‘live’ is probably not so. The spectator’s awareness of illusion serves to increase the sublime affect rather than diminish it. So too, the context and setting of this performance – the show-master and the venue along with the play of screens, lights and shadows – are essential in evoking the sublime and the uncanny.

Central to the sublime sensation in this scene from Mulholland Drive is a juxtaposition of ‘presence’ and ‘absence’. Such duality is part of the performance tradition. Pavis (1996: p. 59) describes this in the case of theatre performance in which actors “have a dual status: they are both real, present people and at the same time imaginary, absent characters, or at least located on ‘another stage.’” McAuley (1999: p. 255) believes that the combination of these present and absent worlds as part of the performative act brings about a new state of ‘thirdness’ – an ambiguous hybrid presence that allows one to approach “normally suppressed levels of consciousness”:

[T]heatre undermines the comfortable opposition between reality and illusion, or reality and unreality, absence and presence, here and not-here, now and not-now, and the spectator in the theatre enters into a game that stops this side of madness but that functions to throw into question our “normal” modes of apprehension of the real. Theatre takes place somehow between the opposing terms.

For the purpose of the current discussion, which focuses on performance and dramaturgy, I will make specific use of the terms ‘presence’ and ‘absence’.

‘Presence’ will refer to physical elements of performance: the bodies of the performers and audience, the performance space, the instruments and the props. In the case of Lynch’s Club Silencio, the trumpet player and the singer are marked initially as ‘present’ through their visible appearance on stage, as well as what seems like the physical act of live playing or singing. In performance, ‘presence’ is represented via a living body: the performer plays out a drama through a body that struggles, moves, is acted upon and transformed. The spectators experience ‘presence’ through their own bodies in an empathetic process of identification with the performer. This is very much evident in the emotional and physical intensity of Club Silencio’s singer.

‘Absence’ is manifest in an element of performance that is not a physical entity, but a concept influencing the performance. This could be the notion of a specific absentee: an entity or person that those present are conscious of but who is not physically present (a deity, a deceased person or a famous figure such as the dead composer). Another type of ‘absence’ is a conceptual framework that is regarded sacred or important, e.g. the commemoration of a historical event, a tradition or rite, a structure (such as the score of a composition) or accepted behaviour at an event (such as the very different mores of the classical concert and a rock gig). The ‘absence’ here is the notion that there is something intangible, a communal force bringing the participants together. In Club Silencio, ‘absence’ is manifest in the sound that becomes disembodied; though initially it seems it is very much part of the performers’ bodily ‘presence’, it eventually drifts away from the physical causality, becoming disembodied and therefore ‘absent’.

A performance’s context is essential in making the audience perceive certain ‘absences’ and ‘presences’ as significant. Peter Brook refers to the creation of such a context in his discussion of ‘Holy Theatre’ (1968, p. 63):

All religions assert that the invisible is visible all the time. But here’s the crunch. Religious teaching… asserts that this visible-invisible cannot be seen automatically – it can only be seen given certain conditions… A holy theatre not only presents the invisible but also offers conditions that make its perception possible…

The structures are different – the opera is constructed and repeated according to traditional principles, the light-show unfolds for the first and last time according to accident and environment; but both are deliberately constructed social gatherings that seek for an invisibility to interpenetrate and animate the ordinary.

In order for the play of ‘presences’ and ‘absences’ to occur, the right contextual settings need to be created. Significant elements are highlighted through previous knowledge, convention, drama, narrative, staging or the design of the space. The creation of context is highly dependent on engagement or belief on the audience’s part and an implicit contract between all those present.

Poetic meanings: the uncanny and the sublime

Any live performance consists of a dramaturgy, which, through a process of two-way communication between the creator and spectator, addresses the spectator’s personal world of memories and connotations. This is also the case in electroacoustic performance, and even though the focus is on the element of sound, it is always part of a larger picture that includes more than just one sensation, and relies on the subjective interpretation of the individual audience member. Live performance is always multimodal and includes the space, context, staging and the presence of the performers, and it is within this multimodal set-up that the play between absences and presences can take place. I will focus on two possible poetic meanings or affects that can be evoked through this interplay: the sublime and the uncanny.

The sublime

The sublime marks the limits of our understanding and a way of imagining or sensing what lies beyond those limits, as Shaw states:

[W]henever experience slips out of conventional understanding, whenever the power of an object or event is such that words fail and points of comparison disappear, then we resort to the feeling of the sublime. As such, the sublime marks the limits of reason and expression together with a sense of what might lie beyond these limits (2006, p. 2).

Shaw (2006) provides an overview of how the notion of the sublime has changed significantly throughout the history of the term’s use. For Longinus (Ancient Greece, first century CE), the sublime is manifested in a striking mode of rhetoric (ibid., p. 13-14), for St Augustine (354-430 CE) it relates to the God manifest in the word (ibid., p. 20-21). Kant states that the sublime lies in the cognitive realm and is manifest in the extraordinary power of the mind and imagination to transcend sensual experience (ibid., p. 72-89) while the Romanticists regard the sublime as the possibility of sensing the unimaginable by bridging the distinction between words and natural material objects (ibid., p. 90-114). Postmodernists such as Lyotard and Derrida regard the sublime as a presence that is unrepresentable to the mind, not offering itself to dialogue and dialectic (ibid. p. 115-130), whereas for psychoanalytical theorists such as Lacan and more recently Zizek, the sublime is the embodiment of a lack, manifested in a ‘surplus object’ which cannot fully represent the sublime but actually indicates a failure of grasping it (ibid., p. 131-157). As we can see from these different approaches, the sublime is the result of a tension between an object or a familiar concept (language, natural object, cognitive capacity) and that which cannot be represented or grasped.

The uncanny

Another affect that will be discussed in relation to electroacoustic performance here is the ‘uncanny’, often associated with Freudian psychoanalysis. Freud (1919, pp. 1-2) defines the uncanny as “that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.” Similarly, for Royle (2003, p. 1) the uncanny is the strangeness arising as a result of “a peculiar commingling of the familiar and unfamiliar” and “an experience of…liminality” (Ibid, vii). He lists some possible instances of the uncanny: curious coincidences, loss of body parts, mechanical/automated behaviours in the living, life-like objects, doubles, the uncertainty of silence, solitude or darkness and something hidden or secret coming to light.

The various experiences of the uncanny and sublime, however diverse, have a common theme – a sense of duality between that which is familiar and evident to the senses, and that which is invisible or ungraspable. Such duality can relate directly to the tension between absence and presence in performance. In the following section I will examine several ways in which the relationships between absence and presence in performance can create dissonances or ambiguity leading to a sublime or uncanny affect.

Types of ‘absence’ or ‘presence’ in performance

There are different ways in which an ‘absence’ can be manifested in relation to the ‘presences’ of performance, several of which I will be examining here: evoked absentees, partial absences, doubles and the familiar made unfamiliar. Though this list is not exhaustive, it demonstrates a range of contexts giving rise to different performance dramaturgies. As well as live electroacoustic works, I will place the discussion within a broader context including examples from other types of performance, art and ritual.

Evoked absentees

Some performative rituals refer to specific absentees, such as deities or the dead. A similar reference is made in the musical tradition. Small (1998, p. 197) notes that musical performances have a particular set of relationships “between those present and those significantly absent or perhaps those supernatural beings that are being summoned by the musicking”. The musical performance tradition often evokes the memory of its mythological figures. Concert halls are often fitted with statues of famous composers, or named after them. Issues such as performance ‘authenticity’ and summoning the ‘ghosts’ of the musical past, can become part of the aesthetic experience, or even overshadow it. A composition with a history of its previous performances carries an array of ‘absences’: historical contexts, venues and interpretations. For an informed listener, the piece becomes a sort of re-enactment; performances are compared to famous past performances available as recordings, or, in a more specialised context, to a score.

So too, the sound traces that electroacoustic composers leave behind are a possible evocation of the past when re-played. The affects and meanings of sound reproduction have long been an area of interest in sound studies, as evident in the work of Kittler (1999, pp. 21-114) and Sterne (2003). The use of recorded sound as part of a live performance can give rise to connotations not only with the aesthetic and cultural context of the composition, but also the historical context embedded in the recording technology used. Stockhausen’s piece Kontakte (1958/60), with all its nuanced complexity, carries a trace of an electronic studio in the 1950s. A live performance of the piece is therefore a mixture of the here-and-now (via the live instrumental parts) with a time gone by (via the ‘tape’ part as well as the composition’s aesthetics). A sense of nostalgia can also explain the appeal of ‘retro’ sounds and the equipment that produces them such as analogue synthesizers.

Citation is also a means of evoking the past. Music that has been kept in the form of a score allows for renewed performance, as well as citation. In his piece Sinfonia from 1968/9, composer Luciano Berio quotes profusely from pieces such as Mahler’s Second Symphony, Debussy’s La Mer, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and many others, with appropriation forming an important layer in the composition. Part of our musical past has also been kept in the form of sound recording; the whole history of recorded music is potentially at a musician’s disposal (the issue of copyright providing the only limitation). Recordings are fragments of a time and a place. A new piece can either clearly refer to the past, or alternatively try to reassemble it. Referring to the past can also be a tribute; it can evoke nostalgia or work with particular cultural connotations and narratives.

Charles Dodge utilises nostalgia for the absent in his Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental (1980) for live piano and tape, based on a recording from 1907 of legendary singer Enrico Caruso. The recording was restored and resynthesised into a hybrid of man and machine. This piece is usually performed in a live context, with the live presence being the piano accompanist. The soloist in this case is the invisible, ghost-like ‘appearance’ of the legendary singer electroacoustically brought back to life. As the composer testifies1:

In the course of the work the voice searches for an accompaniment and is heard at different times with the original band, with electronic sounds, with copies of itself, with the live piano, and with combinations of them all. There is a surrealistic, dreamlike aspect to these apparent dislocations. The initial efforts are humorous; as the work progresses other emotions come into play.

Other than actual human entities, a different time and place can also be evoked and commented on. Bob Ostertag’s piece All The Rage for tape and string quartet (1993, Sound Example 1) refers to a real life event – a riot in San Francisco in 1991, which followed California Governor Pete Wilson’s veto of a bill designed to protect gays and lesbians from discrimination. The piece starts with a recorded recitation of a text while the string quartet simultaneously plays a tightly synchronised part, which is based on the speech rhythms. The read text sets the scene and helps the listener understand the context, as well as introducing a lucid, moving connection between this context and a more personal expression of anger manifested in the voice of the performer. This section is followed by increasingly manipulated/edited recordings of the demonstration. The string part is at this point derived from sonically notable moments: whistles, screams, voices shouting demo slogans and glass smashing. The string part moves from a clear emulation of the recorded events to material that develops into independent parts. The piece evokes a specific space and time. Placing this material within a context of musical performance expressively amplifies the nature of the issue at hand and creates focus and space for observation and reflection.

Sound example 1: Extract from All the Rage by Bob Ostertag (1993). Performed by the Kronos Quartet and Eric Gupton (reading). The full piece is available from the composer’s website: http://bobostertag.com/music-recordings-alltherage.htm

Partial absences: phantoms, silence and the hidden

Some absences can be marked by gaps or lacks in the manifestation of ‘presence’. I will look at three cases:

- Phantoms: in which there is presence in one sensory modality, but absence in another.

- Silence: which is juxtaposed with sound, for instance, through long pauses between sound phrases

- The hidden: where part of a presence is revealed but another part of it is not.

Phantoms are created through absence in one modality and presence in another, or as Merleau-Ponty (cited in Chion 1994, p. 125) points out, “a ghost is the kind of perception made by only one sense”. This dissonance can be very powerful. One only needs to think of Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream (1893), and its terrifying silent screaming image to understand how effective this can be. Phantoms can appear in a live performance; an organist playing a huge church organ is rarely seen while performing the music. While the sound of an organ reverberating through a large space produces a sense of grandeur, it is the lack of a visible human presence and the sense of an object ‘coming to life’ that enhances the experience of the sublime.

In live electroacoustic performance presences are manifested in sound and vision. By omitting presence in one of these sensory modalities and retaining it in another, one can create ‘phantoms’. As well as the initial surprising uncanny dissonance, phantoms also force the spectator to fill in the gaps, and imagine the invisible presences behind the sounds heard, or the implied sounds behind the visible action.

Volkmar Klien and Thomas Grill’s installation Relative Realities (2007) works with such phantoms of partial absence. It consists of a large pendulum swaying through space and ‘colliding’ with virtual objects which, though not physically present in the space, are represented through electroacoustic sound. The tension between a physical impression of the objects via sounds spatialised precisely within a three dimensional space, and the clear absence of actual objects in the space, creates a sensory dissonance. Another uncanny phantom-like effect is produced via the video element of the installation: a screen mounted on the pendulum providing a moving ‘window’ to another ‘absent’ space that is different from that of the gallery.

Film example 1: Relative Realities – an intermedia installation by Volkmar Klien, in co-operation with Thomas Grill

A phantom-like impression can also be created when a voice is separated from the body that produces it. Such disembodied voices are often used in film. Chion uses the term acousmêtre to describe a voice without a visible body – a voice that is neither inside nor outside the image (1994, p. 129). The acousmêtre is not inside the image, as the source is not seen, but not completely outside it, as it is part of the narrative and might at any point enter it. There is a constant flux in the relationship, and this delicate balance is what makes the acousmêtre an uncanny, ambiguous entity. In my piece Safari TV (2009, Sound Example 2) for electric guitar, two laptops and soundtrack, there is a central role for a ‘hidden’ disembodied voice representing the machine or system of the game. There is something menacing about this voice; it explains the rules of the game, encourages or admonishes the guitar player, teases and intimidates (“I can see you. You can’t see me. But I’m here. I am watching you. We are all watching you.”) Finally it invites the guitar player to join ‘the team’. A manipulation of the recording (delays, various reverbs, filtering, harmonisers) indicates an ever-changing space and highlights certain characteristics, making the voice both present but never quite located ‘here’ in the live situation of the stage. Its invisibility adds to its authority as well as ambivalence: who is this voice? Is it machine or human? Who is behind it? What system of power does it represent? How come it commands and influences so blatantly? This ambivalence might not have worked with the human source of the voice physically present and visible on stage.

Sound example 2: Safari TV (2009) by Guy Harries. Performed by the POW Ensemble: Wiek Hijmans (electric guitar), Luc Houtkamp (laptop), Guy Harries (laptop) and Han Buhrs (recorded voice).

Figure 1: Safari TV performed live (Photograph: Adri v.d. Berg).

The tension between absence and presence can also be manifested via juxtaposition in the time domain, as gaps of silence. In several of Morton Feldman’s pieces the composer introduces lengths of silence between instrumental gestures. His piece Rothko Chapel (1971) for viola, solo soprano, chorus, percussion and celesta evokes absences on many different levels. The piece was written in memory of Feldman’s friend the artist Rothko who had committed suicide. As Alex Ross (2008, pp. 530-31) points out, the piece also refers to the ‘voice of God’ in Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron, to Stravinsky’s Requiem Canticles and a melody reminiscent of the synagogue. Instrumental passages provide a ‘frame’ for the silences: the presence of sound prepares the scene for an ‘absence’ manifest in periods of silence. In a sense, a phantom of sound spills over into the silent passages. The audience has the active role of imagining sounds, or the possibility of their occurrence.

An extreme example of silence made evident by context and human presence is, of course, John Cage’s piece 4’33. The score of the piece is playable by any musician on any instrument. The setting is musical: there is a performance, a score and an instrument. Once the expectation of sound is created through the physical presence of a performer and an instrument, silence becomes meaningful. Silence here is not total; one can still hear sounds of the surrounding environment. However, the moment can be perceived as silent due to a lack of the sound that we expect to hear. Similarly, Stan Link considers silence as conceptual. Even though there is no such thing as complete silence, we have a notion of what it should be, and that notion is absolute. As Link maintains: “Our impression of the impact and meaning of silence in a musical context is […] heightened by a sense of transcendence: the ideal silence banishing the real” (1995, pp. 219-20). Silence here is an absence, a transcendence that we can only conceptualise by imagining it through its imperfect copy in the real world. It is this dissonance of a conceptualised ideal and a reality that imbues silence with meaning.

A juxtaposition of absence and presence also occurs in the act of hiding and revealing, where, again, the audience is invited to fill in certain gaps. In the case of live performance, a performer is often hidden and separated from the audience until it is time to start the show. Degrees of veiling and unveiling can also be used as expressive means during the actual performance. The last part of George Crumb’s piece Night of the Four Moons (1969) for alto, alto-flute, banjo, electric cello and percussion ends with a sustained cello harmonic at which point all of the performers except the cellist walk off stage while playing their final phrase. The now-hidden instrumentalists continue playing their last parts off-stage and the music is “to emerge and fade like a distant radio signal” (Crumb), thus representing a simultaneity of two musics: the cellist’s ‘Musica Mundana’ (Music of the Spheres) and the offstage ‘Musica Humana’ (Music of Mankind). Composed around the time of the Apollo 11 space mission and inspired by it, this point of the piece conveys a sense of duality between separate embodied and disembodied worlds. The absent, disembodied world here is that of the instruments off-stage playing a melody resembling a lullaby, evoking a sense of yearning for home that appears to be far away.

Doubles and parallel worlds

Electroacoustic sound can evoke a world that is parallel to that on stage – one that suggests other spaces, objects and human presences. In a sense, the audience perceives a doubled world: the real-embodied and the virtual-disembodied. I will examine two types of electroacoustic doubling: ‘strange’ doubling of the live performers, and the creation of a sonic mask that creates a doubling of a performer’s identity. In these cases, the ‘disembodied’ double creates an uncanny affect.

‘Strange’ doubling of presences

Marko Ciciliani’s piece J&J (1996/7) for mezzo-soprano, piano and electronics is a postmodern exploration of the song tradition. As the composer points out (Ciciliani nd), a sense of duality pervades the piece. This is evident in the juxtaposition of two different texts – a Grimm fairy tale, and a contemporary text about people trying to reach each other by phone. A duality is also evident in the relationship of the two musicians, as well as the way the electronics relate to the live part. The electronic part consists of recordings of the singer, as well as an electronic piano sound controlled by MIDI. These electroacoustic sounds are played from loudspeakers attached to the resonating body of the piano. The recorded voice adds an extra layer of meaning, as well as the presence of invisible speaking characters. The electronic piano part doubles the live piano sound, and at times moves from the familiar to the unfamiliar when it is detuned by a quarter tone. There are two layers at work in this performance – one that is easily associated with the familiar art song tradition of the Romantic era complete with a singer and piano, and a second layer that is an eerie doubling manifest in the invisible world of recorded voices and piano sound made uncanny by the addition of mediated piano sound and detuning.

Sonic masks

Another type of doubling, both metaphorically and physically, is the use of a mask. The mask has been used in many ritual traditions. Performance theoretician and theatre maker Schechner (1977/2003, pp. 43-44), describing the Hevehe ritual of the Elema people in Papua New Guinea, points out how the masks worn as part of the ritual help create a doubled perception of two co-existing parallel worlds: one being the world of the Hevehe masks and the imaginary entities which those wearing them are supposed to represent, and the other being the reality of the villagers’ everyday lives:

In theatrical terms neither the performed (masks) nor the performers (villagers) is absorbed into each other; one does not “play the role” of the other. They stand whole and yet autonomous… Both move freely through the same time/space. The realities confront, overlap, and interpenetrate each other in a relationship that is extraordinarily dynamic and fluid.

The participants negotiate the two worlds and fuse them, while still being aware of the two separate realities. But what is the electroacoustic equivalent? We can consider real-time processing of a sound played live, instrumental or vocal, as a sonic ‘mask’. This impression is most strongly evoked if electroacoustic processing is simultaneous with the original sound: the connection between performer and sound is evident, yet somehow de-familiarised and rendered uncanny. An example of the mask reflected both in a visible, physical object and in sound transformation can be seen in the Star Wars character Darth Vader. The mask in this case both hides the face and transforms the voice. Both of these erase the impression of the character’s humanness. It is only after his death that the character is unmasked and revealed to be the protagonist’s father, both fragile and human (Return of the Jedi, 1983). In this example the mask causes a partial acousmatisation of the voice, as the source is partly hidden; we cannot see the mouth or any facial expression.

Indeed, in a way similar to the visual effect of a mask altering an aspect of one’s appearance and perceived identity, in the domain of sound the timbral quality of a voice (or an instrument) can be altered, thereby influencing the possible connotations of gender, age, machine/human hybrids or size. An example of this is Laurie Anderson’s use of voice-altering devices in creating different characters and alter-egos in her live performances (Jestrovic 2000).

Familiar turns unfamiliar

As we have seen, the sublime and the uncanny are often associated with the unfamiliar. In electroacoustic music, though there is an increasing familiarity with new technologies, there is the potential of creating unfamiliar performance scenarios. However, a suitable context needs to be created in order for the unfamiliar to be perceived as significant and part of the poetics of the dramaturgy. Stockhausen (1988 cited in Lalitte 2006, p. 109) suggests that the combination of the familiar and unfamiliar creates such a context:

[T]he meeting of the familiar, the named, in the areas of the unknown and the unnamed, confers the earlier growing mystery and fascination. And conversely, the well-known, even the banal, the old, to which we hardly pay any attention, gets fresh and alive again in the new environment of the unknown.

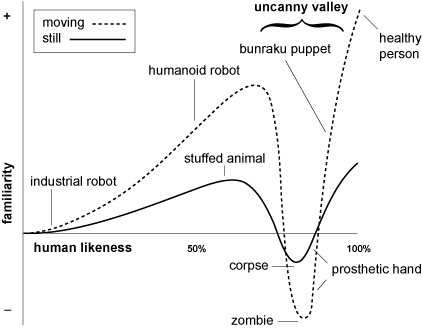

Applying such a tactic to the cultural perception of technology, we can trace strangeness to the areas where a technology is still new, unexplored and potentially dangerous. The combination of the familiar human body and the unfamiliar machine extension can be uncanny. According to Mori (1970), the human likeness of a certain object such as a robot or a prosthetic body part can arouse a positive feeling, but only until a critical point, at which time there is a strong sense of repulsion, which he calls the ‘uncanny valley’ (see Figure 2). There seems to be a dissonance between the seeming familiarity of the object having human-like traits and the realisation that this is not truly the case. Similarly, this sense of ambiguity and discomfort can be created in the juxtaposition between the human performer on stage and the ‘other’ presences that are his/her extensions.

Figure 2: The ‘Uncanny Valley’ (Mori 1970)

Electroacoustic methods can alter the perceived causalities relating the performer to the sound. When a connection to a performer is established via causality (thus marked as ‘familiar’), but the causality is then disrupted in some way and becomes unfamiliar, a sense of the uncanny is evoked. In Simon Emmerson’s piece Spirit of ’76 (Sound Example 3) a solo flautist plays an instrumental part which is recorded in real time and played back using a tape machine (or a Max/MSP patch in more recent versions) creating a highly uncanny effect, as the composer suggests (Emmerson 2006, pp. 212-15):

Most notably, sum and difference tones are created ‘live’ in the room; they seem to be present but ‘strangely’ located somewhere around your head and ears. Many of these are lower than the lowest performable note on the flute.

The structure of the piece introduces an ever-increasing intensity in dynamics, texture, and movement from high to low pitches, as well as rising psychological tension. Towards the end, a massive block of sound is created and then cut off abruptly just before the tape reaches its physical breaking point. In this piece the sound realism of the flute performance is broken by the addition of tones (some of which cannot be produced by the flute) and the strange psychoacoustic impression, produced by sum and difference tones, of sounds seeming to be located around the head of the listener rather than the performance space. The audience experiences an uncanny transition from the familiar flute sound within a concert performance to the almost-invasively unfamiliar.

Sound Example 3: Extract from Spirit of ’76 by Simon Emmerson. Performed by Nancy Ruffer (flute) and the composer (electronics) 1983. Courtesy of the composer.

Transformations

We have seen how the interplay between ‘absence’ and ‘presence’ can occur in a parallel, synchronous fashion through the process of doubling, or in the case of evoked presences or phantoms – through a lack that is created by a presence that implies it. Another means of manifesting the play of ‘absence’ and ‘presence’ is through transformation in time occurring either as a sudden rupture, or gradually.

A process of disembodiment or re-embodiment is a powerful method of transformation with a strong dramaturgical resonance. Chion (1994, p. 131) alludes to such a transformation in the de-acousmatisation of the voice in cinema. In film, the acousmêtre, a disembodied voice, might at some point in the narrative ‘find’ a body. A villain whose voice we have heard but whose face we have never seen, or a narrator whose voice has led us through the film, is finally revealed. Chion (ibid., p. 131) suggests that “the de-acousmatisation of a character generally goes hand in hand with his descent into a human, ordinary, and vulnerable state”. The reverse process of acousmatisation is another method in which the sound ‘leaves’ its body source, which we have seen in the example of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. The full presence of sound and its apparent cause turn into a phantom – a sound that continues once the human agency is no longer ‘co-operating’. A series of acousmatisations and de-acousmatisations also occurs in Trevor Wishart’s Vox 1-4 (1980-87, recording 1982-88). In these pieces for vocal ensemble and tape, the live vocalisations start out merging in an almost indistinguishable fashion with the tape. Gradually, the tape sound is transformed into other source-bonded types, such as thunder or a swarm of bees, only to eventually reconnect with the timbres of the live vocalisation. Sounds seem to float in and out of embodiment, as though they are an ephemeral presence, travelling from the visible to the invisible and back. Though familiar source-bonded sounds are used, there is hardly a sense of realism or representation, but continuous flux that has nothing to do with the real world, evoking an eerie, surreal impression.

Conclusion

The integration of electroacoustic sound in live performance has not only expanded the palette of sounds available to the performer; it has had a far-reaching influence on the dramaturgy of performance. The redefinition of performative causality, as well as the interplay of embodied and disembodied entities have opened up a world of new narratives and poetic meanings. Through the discussion of various performative works, we have seen how the duality of embodied ‘presence’ and disembodied ‘absence’ can be used to create poetic affects such as the uncanny and the sublime. The ambiguity of electroacoustic sound’s relation to physical presences can evoke the uncanny allusion to other spaces, personalities and events (e.g. Ostertag’s All the Rage), or create ‘phantoms’ that are only partially present in the space (Klien and Grill’s Relative Realities and the acousmêtre in the author’s composition Safari TV). It can de-familiarise situations through unexpected tranformations (e.g. Emmerson’s pieces for flute and live electronics Spirit of ’76), or provide an additional layer that acts as an eerie doubling of the space and characters on stage (e.g. Ciciliani’s J&J). The uncanny and sublime affect are only two examples of many meanings and narratives that can be constructed by utilising the particularities of the electroacoustic sound on stage. However, they demonstrate its potential in the construction of dramaturgy.

In this article I have attempted to advocate a live electroacoustic practice that goes beyond technological tools or sound composition, and examines the meanings and affects that are part of the live performance’s dramaturgy. Such a dramaturgy focuses on the experience of the live event, and includes the space, movement, staging and body, as well as the construction of meaning, all of which are inseparable from the music and sound. It is therefore important that live electroacoustic practitioners adopt a broader view that is aware of the wider spectrum of performance art and theory and draw on the methodologies developed within these traditions.

Footnotes

- http://artofthestates.org/cgi-bin/piece.pl?pid=37 [↩]

References

Brook, P., 1968. The Empty Space. London: Penguin Books.

Chion, M., 1994. Audio-Vision: sound on screen. New York and Chichester: Columbia University Press.

Chion, M. 2006. (trans. Julian, R. and Selous, T.) David Lynch: 2nd Edition. London: BFI.

Ciciliani, M. (nd) J&J for mezzo-soprano, piano and live electronics composed in 1996. Available from: http://markociciliani.de/archive/j_j.html

Crumb, G (nd) The Compositions: Night of the Four Moons. Available from: http://www.georgecrumb.net/comp/night4-p.html

Dodge, C., 1980. Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental. Performed by Alan Feinberg (piano). New Albion 1994, CD NA043.

Emmerson, S., 2006. ‘In what form can “live electronic music” live on?’. In Organised Sound, 11:3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Emmerson, S., 1976. Spirit of '76. Performed by Nancy Ruffer (flute) and Simon Emmerson (live electronics) 1983. Courtesy of the composer.

Freud, F. (trans. Strachey, A.), 1919. The Uncanny. Available from: http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf

Fontana, B. (nd) The Relocation of Ambient Sound: Urban Sound Sculpture. Available from: http://www.resoundings.org/Pages/Urban%20Sound%20Sculpture.html

Harries, G. 2009. Safari TV. Performed by The POW Ensemble.

Jestrovic, S. 2000. ʻThe Performer and the Machine: Some Aspects of Laurie Anderson's Stage Workʼ. In Body, Space & Technology 1:1. London: Brunel University.

Kittler, F. (trans. Winthrop-Young, G., Wutz, M.) 1999. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Klien, V. and Grill, T. (nd) Installations and Interventions: Relative Realities. Available from: http://www.volkmarklien.com/installations/rel_rea.html

Lalitte, P., 2006. ‘Towards a semiotic model of mixed music analysis’. In Organised Sound 11:2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Link, S., 1995. ‘Much Ado About Nothing’. In Perspectives of New Music 33:1/2. Seattle: University of Washington.

McAuley, G., 1999. Space in Performance: Making Meaning in the Theatre. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Mori, M., 1970/2005. The Uncanny Valley. Available from: http://www.androidscience.com/theuncannyvalley/proceedings2005/uncannyvalley.html

Norman, K., 2004. Sounding Art: Eight Literary Excursions Through Electronic Music. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate.

Ostertag, B., 1993. All the Rage. Performed by the Kronos Quartet and Eric Gupton. Elektra-Nonesuch 1993, CD 79332-2.

Pavis, P., 1996. Analyzing Performance. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Ross, A., 2007/2009. The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century. London: Harper Perennial.

Royle, N., 2003. The Uncanny: An Introduction. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Schechner, R., 1977 rev. 1988, 2003. Performance Theory. New York and London: Routledge.

Schroeder, F., 2009. ‘Dramaturgy as a Model for Geographically Displaced Collaborations: Views from Within and Views from Without’. In Contemporary Music Review 28:4/5. Abingdon: Routledge.

Shaw, P., 2006. The Sublime. Abingdon: Routledge.

Small, C., 1998. Musicking: the meanings of performance and listening. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Sterne, J., 2003. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Stockhausen, K., 1959-60. Kontakte. Performed by Koenig, Stockhausen, Caskel, Tudor. Wergo. CD WER6009-2.

Wishart, T., 1982-88. Vox. Performed by Trevor Wishart and Electric Phoenix. Virgin Classics 1990, CD VC791108-2.

About Any Resemblance is Purely Coincidental by Charles Dodge (nd). Available from: http://artofthestates.org/cgi-bin/piece.pl?pid=37

Mulholland Drive, 2001. Directed by Lynch, D. [DVD]. STUDIOCANAL / The Picture Factory.

Return of the Jedi, 1983. Directed by Marquand, R. [DVD]. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank my PhD supervisors Katharine Norman and Laurie Radford who helped me develop the ideas presented in this article. I would also like to thank the composers Simon Emmerson, Bob Ostertag and Volkmar Klien for allowing me to include extracts of their work.

Bio

Guy Harries is a composer, sound artist and performer, working with electronics, acoustic instruments, voice and multimedia. He has produced a number of multimedia works: Stereo Dogs (2002), Nocturnaround (2004) and Imaginary Friends (2008). His multimedia opera Jasser, toured throughout Holland in 2006/07, and his chamber opera Two Caravans won the Flourish new opera award and was produced for the stage in 2013 by OperaUpClose and Kameroperahuis NL. He has also created a number of participatory sound and image installations, including Shadowgraphs (2009, Stephen Lawrence Gallery) and Erotolalia (2011, Prince Charles Cinema). He completed his PhD in Electroacoustic Performance at City University, London and is a senior lecturer in music at the University of East London. For more: www.guyharries.com